In case you choose to investigate me like Jonah Lehrer—I’m that important—I should warn you that a few of these concepts and jokes have been recycled from a blog post I wrote last year for my own site, The Anti-Girlfriend. There are only so many rib jokes out there.

In this week’s Torah portion, which is the first of the year as the cycle of readings renews after Simchat Torah, we encounter the creation of the world, the animal kingdom, man and then finally woman from man’s rib.

As a young yeshiva student, I never learned the obvious feminist critiques of this particular allegory even if the narrative was at times subtly presented as a reason for the “natural” pecking order—men in dominion over women. According to this view, Adam is the earliest known venture capitalist with an eternal equity stake in women’s bodies. In other words, a very early forerunner of the Republican Party.

Rather, my teachers explained it from the matchmaking perspective. Adam was lonely and noticed that everyone else—all of the newly created animals—had a complement. Bulls had cows. Male monkeys had female monkeys. (I suppose he Adam could’ve been patient until some of those female chimps evolved into suitable partners, but he was solidly in the Creationist camp.) Like the lead female character in every romantic comedy for the last twenty years, he was tired of being stuck alone at the singles table. But there were no sassy gay best friends back in those days, so he took his grievances to the Ultimate Wingman—God.

“God,” Adam said shrilly, “all of my friends are married. It’s not fair.”

As most know, God then put Adam to sleep and created a wife, Chava, from his rib. And because of this, men are compelled to seek out their missing rib in the form of a wife, who was created from it. In Bereishit it is written: “On account of this a man leaves his father and his mother and clings to his woman.”

Superficially, it’s actually very cute—the orthopedic equivalent of those “best friend” necklaces you used to wear in middle school, with each friend wearing one half heart until the inevitable falling out over a guy or a nasty text.

It’s also nice to read a narrative where the man is depicted as the needy one, desperate to meet a mate, the one made to feel that there are simply no suitable women out there for him to mate with. (“I’m sorry,” Adam’s simian best friend must’ve said. “I just don’t know of a girl for you. All the women I know are married and apes.”)

But as a modern woman, the orthopedic soul mate narrative is troubling, and not just for the popular domination/subjugation narrative it supports. The biblical origin story of Adam, his rib, and the male quest to find a “helpmate” also provides some scriptural basis to the “dating” rules—that the man should be in pursuit and that a woman is supposed to wait around until a guy comes around and identifies her as the possessor of his rib.

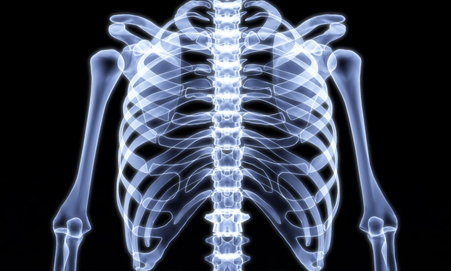

I know it might seem like I’m taking this whole “rib” allegory too seriously, but as a result of medical experience, I’ve been forced to give this body part a lot of thought. You see, one third of my bottommost floating rib on my left side was removed and placed in my spine to fuse my spine. “I’m creation, upended,” I joked with my friends.

When I was 14, I was diagnosed with scoliosis, but mine was not the Judy Blume version of the spinal abnormality. I was no Deenie. Hers was relatively moderate, correctible through a brace. Mine was quite severe. By the time it was diagnosed, it was already in the operable range—above 50 degrees. A few months later when I underwent the procedure, the curve had jumped to 72 degrees. I was getting pretty close to being contorted into a right angle.

Typically, the surgeon removes a bone chip from the patient’s hip and breaks it into even small chips, which are then inserted in between the vertebrae. Like the two parts of a broken arm knitting back together, the bone chips fuse to the vertebrae, creating one solid, immoveable mass, correcting and arresting the growth of curve. Then titanium rods and screws are then inserted to act as internal cast.

But since my surgeon elected to perform anterior and posterior fusion on me—mostly due to the fact that I resolutely refused to wear a brace after the surgery—he removed a third of my rib since he was already in the anatomical neighborhood. Instead of being created from someone else’s rib, I was mended by own.

In the immediate aftermath of the procedure, I didn’t give this much thought. I didn’t think about what lay underneath the scar that stretched from behind my rib cage to mere inches from my navel. Mostly, I was horrified by the sight of it, collapsing in hysterics when the bandages were first removed.

But as the years progressed, I changed my tune when it came to the scars. (The other one runs down two-thirds of my spine.) I came to regard them as badass—signs of my ability to overcome a major physical setback. A year after the fusion, I went back to my beloved sport of gymnastics. In my mid-twenties, I added break dancing to my athletic repertoire.

Still, I didn’t give my ribs much thought until a couple of years ago when I started feeling intense pain and tightening in the left side of my chest. I thought I was having a heart attack and went to my doctor in tears. I was 27, a quasi-vegetarian who worked out five times a week with no family history of heart disease or problems. I couldn’t understand how this could be happening to me.

Thankfully (and as my doctor expected), my heart was not the problem. My ribs were. Specifically the ones on my left side were not as mobile and flexible as they needed to be in order to expand and contract for breathing because the muscles around them had tightened up. “Why the left side only,” I asked “and not the right?”

“Because you’re missing a part of your rib on the left,” the scoliosis specialist answered. “The muscles there have less skeletal support.”

And for the first time in thirteen years, I really missed that little piece of my rib.

I guess this means I sort of understand guys a little better—the need to pursue that missing piece of you. Of course, I don’t have to look much further than my back for my missing piece, but that’s really difficult. It’s really tough for me to twist because of the titanium and screws in my spine.

Anyway, I guess I’ll have to pursue my missing rib the way the men have—by pursuing a mate. Can you really blame me? I’m rib deficient, just like the boys.

You made some respectable points there. I appeared on the web for the difficulty and located most people will associate with along with your website.