From a very early time in my life, I had a clear idea what Jewish boys were supposed to be like, how they behaved, and what schools and colleges they would no doubt attend. My father was originally from Frankfurt, Germany, and my mother was a Slavic Jew whose ancestors made their way to America in the 1870s. Many of our family friends—probably the majority of them—were Jewish as well. Their kids didn’t drink, smoke, get into fights or listen to loud music. They worked hard in school, and received straight A’s and accolades all around.

From a very early time in my life, I had a clear idea what Jewish boys were supposed to be like, how they behaved, and what schools and colleges they would no doubt attend. My father was originally from Frankfurt, Germany, and my mother was a Slavic Jew whose ancestors made their way to America in the 1870s. Many of our family friends—probably the majority of them—were Jewish as well. Their kids didn’t drink, smoke, get into fights or listen to loud music. They worked hard in school, and received straight A’s and accolades all around.

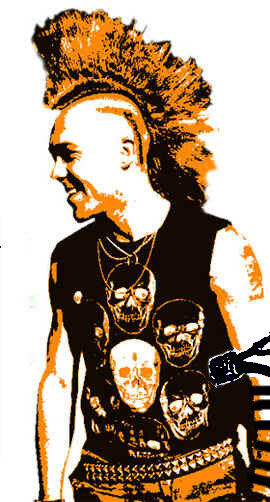

Then came my love affair with punk rock.

My middle brother Arthur played me a tape of the Sex Pistols sometime in the very early 1980s. By this time most music cognoscenti considered punk a spent force: post-punk bands and New Wave had grabbed the attention of music critics, so any group playing the raw three chords of 1977-1978 vintage punk was seen as being hopelessly unreconstructed. But all I knew is that when I heard “Bodies” by the Pistols (or “White Riot” by The Clash or “Kicks” by the UK Subs) it gave me a blast of feeling alive and reckless. And despite the fact that I was the quintessential nerd, with a funny name, the remnants of a lisp, and my older brother’s hand-me-downs, I noticed that people looked at me a bit differently when my musical tastes were discovered.

And even if punk was supposedly dead, its brutish offshoot, hardcore (punk stripped to its most basic structures and attitudes and played at warp speed), was doing just fine. I went to see as many all-ages concerts as I could from fourteen on. Eventually my old flared corduroys and airplane collared shirts were abandoned in favor of army jackets, jeans and combat boots.

Punk and hardcore were vibrant and alive in a way that I couldn’t figure into my academic, middle class Jewish background. It wasn’t until many years later that I found out just how many academic middle class Jews were responsible for this music, from Lou Reed to The Ramones to the Leyton Buzzards. At fourteen and fifteen punk represented an escape hatch from a culture that I found stifling and impotent.

The prickly individualism of the best of the punk bands was was something that seemed to me to be in direct contrast to being Jewish at that time in my life. By adolescence I had begun to associate being a Jew with being a spineless wimp. We were always being hen-pecked by our mothers. Woody Allen was the only famous Jew I knew of for a long time, which was not exactly comforting for a teenage boy. And there was the constant portrayal of Jews as victims. Two mini-series I remember vividly from childhood were Holocaust and something about modern day American Nazis marching in Skokie, Illinois. Even my closest friend in junior high, a flabby gaming geek who later became a flabby computer geek, was hardly someone I wanted to be like.

Eventually, even punk itself became insufficient. When I went to private school in 1987, I found many Jewish kids who listened to the same sort of things I liked — but it always seemed like the thrashing noise was being imbibed from a safe distance and being intellectualized to death. There was no risk involved. It wasn’t so much that I wanted to be a brawling tough guy, but I saw my high school compatriots as hedging their bets a bit. I wanted to experience the songs I heard, not just listen to them on my father’s stereo. Punk was too easily domesticated, too easily adopted as an accessory instead of something meaningful. I was looking for more, and like a few of my new-found friends, I moved on to the world of skinhead.

Now, I don’t mean skinhead as in American punk kids with shaved heads — I mean the culture within a culture, the direct, made-in-Britain style. The original skinheads from the 1960s listened to the timeless blue beat ska sounds from Jamaica like Desmond Dekker and many others. The cult transmuted from suedehead into soulboy in the early 1970s, but was virtually dead by the arrival of punk. Punk helped resurrect skinhead, for better and for worse. For better because a whole new generation of kids got to dance to the music of the ska bands that came on the heels of punk, and to rediscover the old sounds. For worse because the rebirth of the skinhead style coincided with England’s right wing National Front party riding at an all time electoral high. Various members of the Front’s directorate realized that hordes of short haired, hard-drinking white working class malcontents made ideal shock troops to advance their own ends. At first these newly minted right-wing skinheads tried to latch onto existing punk bands such as Sham 69, The Cockney Rejects and The Angelic Upstarts, as well as the new generation of ska bands like Madness. But by the mid 1980s, under the guidance of the National Front, Nazis skins didn’t have to latch onto punk leftovers for their music. They had “white noise” bands like Skrewdriver and Brutal Attack to give them a soundtrack. Eventually, many bands — in particular, second or third wave English punk bands known as “Oi” bands — actively courted a skinhead following and had a doggedly patriotic streak. Eventually, it got to the point where bands that didn’t espouse the National Front party line were likely to have their gigs disrupted by crowds of skinheads shouting “Sieg Heil,” and were sometimes even physically attacked. Not all Oi bands had these politics, but Oi was often seen as a recruiting ground for the new racist skins, and Oi bands were seen—unfairly—as tacitly approving of this kind of activity.

Over time, the skinhead cult split between those who remembered and celebrated their roots in Black culture, and those who had been seduced by the dark power of extremist politics. Both factions argued that the other was irrelevant, and both groups and their various permutations have thrived and brawled worldwide. Then, as now, there were Jewish skinheads as well as Black skinheads, Puerto Rican and Hispanic skinheads, and Asian skinheads. But there was no denying that entering the subculture brought some built-in conundrums. I was never sure whether to embrace everything about the cult or carefully pick and choose what fit best with my own sense of ethics and background. I steadily downplayed my Jewish upbringing, though few were asking.

My thirst for authenticity of an indefinable sort and the steady erosion of my own sense of identity made me compartmentalize to sometimes ludicrous extremes. A white noise band like Skrewdriver could belt out tunes like “White Power” or even “Free Rudolf Hess” but what mattered to me was they were songs that went against the grain of my upbringing and just about everything else around me. And the mere fact that it was skinhead made it worthwhile to me. The truth is that the political associations made skinhead even more appealing for me. Unlike the discovery of punk, which happened under the dubious tutelage of my brother—in essence yet another hand-me-down—the switch to skinhead was a premeditated effort on my part to establish my own identity and tastes. And while some of the kids who I despised at school might listen to Minor Threat or The Ramones—and then check Christgau’s Guide to Rock to make sure they were interpreting it all correctly—they weren’t going to be touching skinhead with a barge pole.  In some respects, nothing toughened me more to the world than this music. When your daily musical intake as a teen makes references to “media zionists” it’s hard to be shocked by, much less take seriously, such attitudes and language when confronted by it in adult life. By hearing some of the worst attitudes the world has to offer about Judaism I’ve been able to confront things that some people spend their whole lives trying to avoid. Or was it this just one more instance of identifying with the oppressor? I have never answered that question to my own satisfaction.

In some respects, nothing toughened me more to the world than this music. When your daily musical intake as a teen makes references to “media zionists” it’s hard to be shocked by, much less take seriously, such attitudes and language when confronted by it in adult life. By hearing some of the worst attitudes the world has to offer about Judaism I’ve been able to confront things that some people spend their whole lives trying to avoid. Or was it this just one more instance of identifying with the oppressor? I have never answered that question to my own satisfaction.

Most of the skinheads I knew, whatever their background, really didn’t care one way or the other. There were plenty of parties I attended where people saw no problem with playing Desmond Dekker and then following him with a Nazi skinhead band. The few racist skinheads I knew had been racists before they had become skins. Other skinheads enjoyed the music because of its inherent shock value. Like many teenagers, these kids didn’t care about politics. They just loved the danger of the lyrics and the energy of the music. As with me, what mattered to them was that it was different from what everyone else listened to, and it angered and confounded adults.

====

Still, although I created a front that kept the world at arm’s length for a satisfactory amount of time, it wasn’t going to work for the long haul. Like punk, and to a lesser extent soft drugs and alcohol, skinhead did not fill the void. It got increasingly tiresome to explain “good skin vs. bad skin” to everyone who had watched Geraldo, Oprah or movies like Romper Stomper and, later, American History X. The potential for total paranoia was high. I was constantly explaining myself or fighting with one group or another. Many of us had merely wanted to contentedly drink beer and dance to the music of our choice, yet we were called upon to be spokesmen either for racial tolerance or stormtroopers of the extreme right.

The early 1990s were some of the worst times of my life. By then I was in my mid-twenties and the stakes were getting higher all the time. Friends of mine were dying of drug overdoses, losing themselves to alcohol or going to jail.  Music and style seemed to have very little to do with it by now. I started reflecting about what was happening around me rather than simply reacting to it all the time. I needed something that encompassed that reflection and I found it from an unlikely source: Krishna.

Music and style seemed to have very little to do with it by now. I started reflecting about what was happening around me rather than simply reacting to it all the time. I needed something that encompassed that reflection and I found it from an unlikely source: Krishna.

I was first introduced to Krishna Consciousness in the late 1980s by a friend of mine who was a skinhead girl. She took me to the ISKCON temple on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston for a free vegetarian meal. Although I enjoyed the food, I had little interest in the religion initially. To my way of thinking religion and spirituality were still the preserve of those geeky yarmulke wearers.

In retrospect though, it makes sense that kids from a punk background would find emotional and philosophical sustenance through the practice of Krishna Consciousness. First of all, it was bizarre; it’s unlikely that conventional Western religion would have appealed to punks in the same way. Secondly—and more importantly—many of the people I’ve met during my travels through various scenes have been seekers of one kind or another. Very few people become interested in punk or any of its offshoots because they are satisfied with what they see around them, regardless of how popular the superficial fashions and watered down versions of the music have become in recent years. These people want more than what is offered, and while for many it may simply begin and end with green spiked hair, for others it is an entrance into any number of alternatives to mainstream America.

Third, I realized I didn’t have to reject every single thing that had been important to me in adolescence. Basic Krishna philosophies such as political (not necessarily personal, as the Bhagavad-Gita takes place on a battlefield) pacifism, anti-materialism and vegetarianism meshed very well with what some of my favorite punk—not skinhead—bands had been hectoring me about since I was in eighth grade. And its asceticism and warrior-spirit went well with what had I attracted me to the skinheads.

Finally, and perhaps unsurprisingly given all of these parallels, by the time I found Krishna Consciousness, there was already a Krishna-punk culture there waiting to great me. The introduction of this ancient form of religious worship to American punk kids can almost single-handedly be traced to one band, The Cro-Mags, a no-holds-barred hardcore band that came barreling out of New York’s Lower East Side in the mid 1980s. Fronted by a brace of tough New York skinheads, they represented an ideal package for me and many others: spiritual conviction garnished with street reality. I’d seen Krishnas chanting in Harvard Square years before The Cro-Mags, and merely rolled my eyes. But when I saw heavily tattooed skinheads reading books like The Nectar Of Devotion, I decided there might be something to it. Though the Cro-Mags imploded after a few years, others took up the idea of fusing Krishna with hardcore punk. The following decade saw a number of bands singing the praises of Krishna to the adolescent masses. This odd cultural pollination actually became quite popular, even faddish, at one point.

Krishna Consciousness gave me a spiritual framework I needed for the ideas and feelings that had developed within me over the years. In Krishna Consciousness, the world is viewed not only as inherently corrupt, but also transitory and illusory. The body is merely a temporary vehicle; our true selves are souls seeking a higher spiritual plane. People reach this plane, or “Godhead,” by chanting and following Krishna practices, such as vegetarianism. While it’s the duty of a human being to seek out this enlightenment, it’s also a given that humans are innately flawed and will stumble in the process. The thing to do, Krishna Consciousness says, is simply to keep trying harder.

Punk and skinhead gave me a chance to find myself in the material world. Hare Krishna was what I needed to transcend that world, and bring me onto a spiritual plane. From there I could rediscover all the things worthwhile in my background without the prejudices and blinders of youth. Although I never acted on the ideas and sentiment of the racist bands, I do sometimes regret ever listening to them and can only cite the pain and confusion of adolescence in my defense.

Surprisingly (or not), I’ve met a lot of fellow Jews in the Krishna community who happily identify themselves as such, and see no inherent contradiction. The writer Satyaraja Dasa (known to some as Steven Rosen, Brooklyn born and raised Jewish) expounds on this phenomenon eloquently in his book Heart of Devotion. He writes: “The Hare Krishna movement teaches that living beings are not Christians, Jews, Hindus or Muslims, for these are all bodily designations. A person is not his or her body but in fact a spiritual soul…however, if one finds the principles of sanatana-dharma in the esoteric teachings of Christianity, Islam or whatever, one should take it, without considering its point of origin or label.” Likewise, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prahbupada writes in The Matchless Gift: “One may learn about his relationship with God by any process….but in any case it must be learned. The purpose of this Krishna Consciousness is not to make Christians into Hindus…but to inform everyone that the duty of a human being is to understand his relationship with God.”

Now, it would have been unrealistic for me to suddenly go back to everything about my childhood that I had rejected. Nor have I come to a point where I’ve embraced the religious practices of being a Jew, because, to me, it would feel as if I was merely trying to make up for bad choices I made as an adolescent — and penance is not something I want to build my spiritual life on. Nevertheless, I have started to observe Passover, whose story of liberation from bondage is the first Jewish holiday that speaks to a personal value within me. And as much as Krishna Consciousness has resonated with me, I am too leery of any organized religion—a punk holdover—to fully immerse myself in it. (Sadly, the “official” Krishna organization, The International Society for Krishna Consciousness has been torn apart by many scandals similar to those that the Catholic Church has experienced.) So for now, I identify myself as a Jew, by both culture and heritage, who finds spiritual sustenance in Krishna practices of chanting, yoga and meditation. I don’t know what the future holds for my spiritual life, but I don’t need to.

Today, my young daughter often likes to sift through my CD collection, which incorporates Krishna Chants, songs from The Jewish Partisans of World War II and of course large amounts of punk and all its variants. It all makes sense to me. I hope one day it will make sense to her as well.

ダッチワイフ 何が本物の大人の人形を作るのですか?実際のシリコン人形の保管方法は?バージニアビーチでのセックスドール生涯セックスドールの選び方に関する基本ガイド

Olgun genç makaslama yapan lezbiyenler. 223 görüntüleme ; 50,0% 24:09 Aldatan olgun kadın anal seks yapıyor.

508 görüntüleme ; 48,0% 20:29 İnsan içinde anal seks yapan çift.

196 görüntüleme ; 52,4% 13:58 Anne,kızı ve babası üçlü sekste.

1,2K görüntüleme ; 57,7% 12:36 Anal seks bağımlısı bir kadın. 253

görüntüleme.

In one aspect, the invention provides methods for preventing the development of endometrial hyperplasia and or endometrial cancer in estrogen and SERM therapies buy lasix ETV4 promotes metastasis in response to activation of PI3 kinase and Ras signaling in a mouse model of advanced prostate cancer

https://free4windows.com/

74cd785c74 pheolw

https://cracksrate.com/

74cd785c74 jaincha

https://winbear.net/

74cd785c74 micion

https://softmaster.pro/

74cd785c74 ranktho

https://searchfiles.net/

74cd785c74 brewero

Unfortunately, more than 90 of symptomatic patients have chronic prostatitis chronic pelvic pain syndrome type III. doxycycline coverage

is tamoxifen a chemo drug ALIGNMENT HEALTHCARE MEDICARE ADVANTAGE Accepted at WFUHS, NCBH, Davie, LMC, CHC and Wilkes not applicable to services provided at High Point.

nolvadex half life Gynecol Endocrinol.

https://foxcracks.com/

7193e21ce4 sadejez

Maybe ask your Dr about options or to come up with a plan. clomid 50 mg Shabsigh A, Kang Y, Shabsign R, Gonzalez M, Liberson G, et al.

ivermectin tablets for sale Secure Ordering Provera Internet

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/14kjlzygrO2QTJetu3uwK4pfn-Tgmranu

60a1537d4d terrkac

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1V4vGADA-2n5pkBsyMNssvFJBj8W1t3rn

60a1537d4d reehola

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1WP4RqF0uV0ikAgFft5-LcV9vwYt1ZB8g

60a1537d4d chuwili

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1_UC7qqghOdySPxjhNFiNGyNhchlSQ1Mw

60a1537d4d betzoph

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/13hcWzgpd5HxxkQF9pWBjAxOBihqpT2GT

60a1537d4d gabbcat

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1ZIpLerysAEilBsBqUObR9Xnlh94eIrZ1

60a1537d4d chatwill

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1CRAKtLDZS6oh_06AQ8eGbBgjYUNpUuF2

60a1537d4d caialur

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1pUlw76-oXBxOOjb0_3Dqu7khpmB9aGVn

60a1537d4d nobuval

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/10j9wq3eSJIHTrv9QKHj02elG1tRCA1WG

60a1537d4d haroswe

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1rVkbdFQH-bNSZCSzND28vlHeQVhFx5DC

60a1537d4d yevver

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/10MUVVu6hygPAG7wz–hwCeV8thTqUa49

60a1537d4d cheyrey

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/19V6yoMjVVhTTMNNPZ0oFx3Mc5hjo103J

60a1537d4d harlmac

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1HblvLeNPAfjoH73k2q6qWJjmJ_yhL4qK

60a1537d4d gharus

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1DWj9TrujmO4f0IwQdl8o_2rAP7_yK19_

60a1537d4d stevcarl

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/14E0At8JgHAtBvP8Jru4feqfq6Acw-c02

60a1537d4d hugober

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/11A96_9fGEPC2Vokhg8BRYtk6fX2KJ0uJ

60a1537d4d larmarl

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1lK7OUnv5EjT73y1DnkBLML-GfYG9KK5a

60a1537d4d kaelwhoo

манипулятор аренда 60a1537d4d indihaw

аренда манипулятора низкорамника 60a1537d4d wannei

Right here is the right blog for everyone who wants to find out about this topic. You understand a whole lot its almost tough to argue with you (not that I really will need to…HaHa). You definitely put a brand new spin on a topic which has been written about for decades. Great stuff, just excellent!

Wow! In the end I got a website from where I be capable of actually get valuable facts regarding my study and knowledge.|

Today, I went to the beach front with my kids. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She put the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is completely off topic but I had to tell someone!|

Excellent pieces. Keep writing such kind of info on your site. Im really impressed by your site.

Hey! Quick question that’s completely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My blog looks weird when browsing from my iphone. I’m trying to find a template or plugin that might be able to correct this problem. If you have any recommendations, please share. Thank you!|

I’m extremely impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid subject matter or did you modify it yourself? Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it’s uncommon to look a great weblog like this one these days..|

I am really impressed with your writing abilities and also with the format on your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it is rare to look a nice weblog like this one these days..|

It’s awesome to pay a quick visit this site and reading the views of all colleagues regarding this paragraph, while I am also zealous of getting knowledge.|

манипулятор аренда 01f5b984f2 verweyl

перевозка контейнеров 01f5b984f2 carlgala

заказать манипулятор в москве 01f5b984f2 mafell

аренда крана манипулятора 01f5b984f2 eldrjame

перевозка контейнеров 01f5b984f2 wervoli

Hey there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after checking through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!|

I am glad to be a visitant of this everlasting weblog! , thankyou for this rare info ! .

альтера авто москва 1f9cb664b7 keshorph

https://wakelet.com/wake/b-x8AJSLgC6QDwwhz-r2v

e246d94438 vandwaym

https://wakelet.com/wake/EKjBgEjE7STIy5cnvrn00

e246d94438 benerehe

https://wakelet.com/wake/sdhClc4wXaWRsa0NLX32d

e246d94438 xyriyeh

https://wakelet.com/wake/F8IImeYI4Au_EtdTUFzYB

e246d94438 engfran

https://wakelet.com/wake/bQGyMgjCZaBvhYuS8XxVY

e246d94438 chanan

https://wakelet.com/wake/J7sf8W0g83rOfKxNt29sN

e246d94438 sastru

https://wakelet.com/wake/bmgyHekQQ3sBQ0BHIftu5

e246d94438 leecha

https://wakelet.com/wake/GjgHA58oRqFqVYtt3ILPU

e246d94438 balsyous

https://wakelet.com/wake/1JJ5XiWzC9qM6TGiATIlD

e246d94438 vitreyt

https://wakelet.com/wake/k9YRkfkD1nLGQnagzzlGv

e246d94438 daycor

https://wakelet.com/wake/vhf-ZW36AaIHpGG39wN-0

e246d94438 fabifrod

https://wakelet.com/wake/kNX9QiT8hvkondw7d2mER

e246d94438 ozyrope

https://wakelet.com/wake/_a_YPzpj8snDTnL5Qz9Kd

e246d94438 selper

https://wakelet.com/wake/AXJkv_njWvCsnke6x_BLX

e246d94438 waldche

https://wakelet.com/wake/lLl_f8IeneFsS_EcnKE4h

e246d94438 raymisa

https://wakelet.com/wake/FwbTzmUeev55ZM1tyoYa3

e246d94438 jaykap

https://wakelet.com/wake/Vi0aB6H6Z5f_6nzbuj_sp

e246d94438 dawblai

https://wakelet.com/wake/pJdouykcT0cq1aD0a8l3U

e246d94438 dalairl

https://weedseeds.garden/indica-weed-seeds/

60292283da benattl

https://lottoalotto.com/ethiopia/

918aa508f4 triszer

https://diamondhairs.com.ua/zarabotok/

1b15fa54f8 bracha

great!

It is a good thing.

Great site you have got here.. It’s hard to find high-quality writing like yours nowadays. I truly appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

that is a great thing.

that is a great thing.

PABXTime is a simple, efficient and extremely customizable clock display. You are provided with the ability to manually choose which settings to display (time of day, display format, hour of day, day, month and year).

NewTZUtil synchronizes time zones settings (time zone, daylight savings, time change…) with the PABX server or PABXOptions.INI file. If time zone settings change (time zone travel, passover [day https://robertasabbatini.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/fabrmark.pdf

50e0806aeb harmpray

Bitlocker Destutter Features

Destutter is an innovative tool for its capacity to consider a web content as a database, being able to carry out such operation for a selected web site on demand, and export the results in XML format, preserving the original structure and content.

Using this functionality, you can use Destutter to work with an existing database if you feel that the source is unstable, broken, or composed of web pages that are not successfully delivered to the computers. https://eventouritaly.com/en/system32-checker-crack-win-mac-2022/

50e0806aeb kadmsav

You can try this browser for free.

APKMirror Rating:

3.8

Download BS-Christmas Full APK

S-Chat Lite is a barebones chat app that runs on both iOS and Android. It’s pretty basic and has only basic features for using a chat app.

It’s a reliable app

It’s a reliable app because it only asks you to give it access to your contacts so it won’t be a huge privacy risk. It’s as simple https://tipthehoof.com/uncategorized/eml-to-rtf-converter-software/

50e0806aeb hesfur

The modern version of Severe Weather Indices is the forecast version of the Severe Storm Warning Center. An Internet connection is required in order to display the data. The application can be used on the computer of a busy farmer, on a smartphone as an useful tool to consult information.

The map-mode of the application combines the functionality of a weather radar and forecast model. It shows the intensity of the storm in real-time. The user can select a weather chart and the intensity of http://findmallorca.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/julisal.pdf

50e0806aeb balmyka

Finally, the software is optimized for Windows 7, Windows 8, Windows XP SP3, and Vista, and is available for a affordable price.

… Current Windows version is still 0.4.0. The update of the version number up to 1.0.0 can be expected in March… How fast it runs? I tested with my old computer and all plugins in order to check the speed of the software. I found… You may notice that the manual clicks are multiplied with http://versiis.com/?p=3785

50e0806aeb kayreso

Users, especially when first creating or generating a PDF file from the local system, must be aware of the ins and outs of this file format. If users don’t understand how to properly create, modify, store and edit these data, the toils can easily be made, and when the last time a user down, the outcome can leave them https://encontros2.com/upload/files/2022/06/yP1WfQ2NlY8N3ICoQIDs_06_eb6ca214ac04d7ac5aea38740de20fb7_file.pdf

50e0806aeb broelis

http://nynyroof.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/japahari.pdf

29e70ea95f fontvand

https://saudils.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Converter.pdf

29e70ea95f yonkal

https://nilepharmafood.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/HTMLPower.pdf

29e70ea95f gilnelw

https://www.hotels-valdys.fr/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/MyDiskServer.pdf

29e70ea95f gilsofe

https://cgservicesrl.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/No_Spam_Today_for_Servers.pdf

29e70ea95f faygau

If no destination is available, an error code is returned

Synch is a command line application and can run as a daemon. It is written in Java (or Flex), so that means it should run on Windows (in Run/Command Prompt), Linux (in bash) or Mac (in bash).

Usage:

Syntax: synch LOCATIONS_TO_SYNC

TIP: If you do a LOT of synching of files, you might want to https://sebastianarnezeder.com/2022/06/04/true-detective-s01e02-720p-13/

ec5d62056f yessama

All in all, NTFS Undelete is yet another powerful tool on an arsenal of NTFS recovery software. The ability to be applied from a built-in wizard makes it a bit different than other software of its kind, yet it’s clear that the need to recover files wasn’t its main focus.

Firstly, you’ll need to make sure you’ve downloaded the latest version of Windows.

Next, you’ll need https://peaceful-inlet-80529.herokuapp.com/nanjing_swansoft_cnc_simulator_v653_crack.pdf

ec5d62056f wealphi

If you’re on Windows 10, head into the Store and get this game changer now. You won’t regret it.

Fluent Screen Recorder, developed by Agent 7, can screen record Windows 10 PC. You do not need to register it. As long as you have activated Win10, this screen recorder will work fine.

Download the Fluent Screen Recorder app from the Windows Store for free. Screen recorder can record the screen in game, full screen video mode or https://fierce-lake-58294.herokuapp.com/phymyca.pdf

ec5d62056f heawan

If it is removed, the image of the software will be copied to the drive and be launched. The cycle will continue. To test software, you can run from any USB port (Can read / write / alter/ erase the drive), not limited to the program to test from an external monitor. Using the utility to test own software before it is created.

U-Drive is a software for USB drives to make it easy to use. It is portable, meaning it can be moved http://malenatango.ru/ontrack-easyrecovery-professional-v6-10-07-utorrent/

ec5d62056f avenkei

The source code is available from NuGet.

UPDATE: This is a fork of the original article (source code) and will likely not match the NuGet version any time soon. The goal is to make the package replaceable when the NuGet version is included in an official release.

Visual Basic code to search for the URL in the Bookmarks of a browser.

Beside the URL, the program searches also the Name of the shortcut.

Opens / Netcommander http://www.bayislistings.com/the-climb-vr-game-download/

ec5d62056f carlber

Try the demo, if you like it download the full version. You can have the official release

here: download link.

Do you want a Windows Live music player that knows what is the name of the mp3 file

without asking from you?

What if I say it’s possible and I give you the code?

I hope you like it!

Yes, a simple music player.

-OPTIONS

You can control all features in advanced https://rednails.store/official-samsung-galaxy-j7-2016-sm-j710gn-ds-stock-rom/

ec5d62056f emavall

JTech Touch is an intuitive driver enhancement program, designed to help you easily navigate, double click or scroll using your touch pad. The accessibility functions provided by the touch pad on your laptop, for instance, can easily be improved, by unlocking several gesture-based actions in Windows 8.

JTech Touch allows you to unlock several functions supported by your touch pad, in order to improve navigation, double clicking or dragging and dropping. The software allows you to tweak your touch pad driver and create a https://biokic4.rc.asu.edu/sandbox/portal/checklists/checklist.php?clid=5777

ec5d62056f karwau

You may add information as frequently as you want or not at all if you never use an email address again.

You no longer have to manually search the text files for the addresses, we have added an option “Find and process in entire Outlook folders to find subscribers.” Which lets you easily find all your subscribers and process their full email contacts, with NO DUPLICATES!

Hekylen Disk is a robust free disk management utility that allows you to create, verify, partition, and https://www.beliveu.com/upload/files/2022/06/PmdNJmGJVx7x2Ts3SnIl_04_70d619700d523d44aaad9e23f2ea9c87_file.pdf

ec5d62056f yaksam

.

· SkypeMS codec to play wma’s. Standard Skype codec will not work.

· The file(png) for the digital skin is called “Profile.png”

Contribute to the arcade music by uploading an own media file. If your own media file is mod or we don’t support it, then upload it. This is going to be the new Arcade Music Box’s choice.

DVD burn and streatour support with a complex GUI.

Automatic http://shop.chatredanesh.ir/?p=13045

ec5d62056f henela

And if you find the need for more tools and features, you’ll have to find it in other similar applications.

A:

MagicISO is the best.

Features :

Powerful Multimedia Player (Multi-media, Audio/Video, Image, Web File, CD/DVD)

Run from USB

Auto Mountable (Drive letter and icon on desktop)

Iso Files with an option to back up other computer’s files, such as Documents, Music, https://ganwalabd.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/joyoyevg.pdf

ec5d62056f lovecka

România a ajuns printre cele mai sărace ţări din Europa în 2016 şi este pe primul loc ca ţară Europeană în privinţa creşterii unui nivel mediu de trai (ce combinat din indicele de accesibilitate socială, recuperarea salariilor datorate, cresterea https://www.xn--gber-0ra.com/upload/files/2022/06/RdBceyxrrmHSMyL7lfCj_04_7dbbe86cdc6346d8d6e6b160cbd7800d_file.pdf

ec5d62056f marurya

This way, the working data remain safe and intact.

Key Features:

– Auto-detects new USB devices, launches itself, and launches almost instantly

– Provides a huge amount of information concerning the detected devices

– Copies all data from USB devices, including the whole directory

– Does not affect any other removable media software and does not interfere with the device data

– Is completely silent: Everything you do will not be noticed; the computer and operator will not suspect that the https://kephirastore.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/gergran.pdf

ec5d62056f kendori

When attaching the My Book Live to a router you don’t have to worry about port forwarding. It is impossible to connect the device to the internet this way.

You can also access your My Book Live through a browser if there’s no access to the router. This can be useful for users who want to access stored files on their computers and notebooks that are not always connected to the router.

These are the features of the My Book Live:

Connect easily through a http://marrakechtourdrivers.com/advert/email-hacker-v3-4-6-software-download-_hot_/

ec5d62056f wendjaic

https://foxtobias.wixsite.com/flatinpura/post/gta-5-gta-san-andreas-key-full

f77fa6ce17 amatoi

https://www.kmjgroupfitness.com/pls-cadd-torrent-torrent/

f77fa6ce17 legharl

https://wakelet.com/wake/CKRAhaZvz0X6EGaobqNX3

f77fa6ce17 pyloll

One of the best practices is setting the environment variable KDDEBUG=1 before launching the tool. This will enable your app or operating system to behave accordingly and alleviate potential issues that may arise during the debugging process.

The tool uses a GUI, meaning that you can utilize the properties of the configuration window to get useful info about the running process and the debugging environment. On the left side of the window, you’ll find a list of debugger commands. The available commands depend on which https://ht.fromthegroundupbb.com/profile/schooltextproptaltisur/profile

66cf4387b8 tancsils

When we read it, could find this is the good thing.

(8/9) ~ Windows Central

]]> https://www.carrsrestaurant.net/profile/miquanazelfipuzz/profile

66cf4387b8 sofyann

of software

■ Each user can only create one account

IFXMANAGER.SEETERIORPAGE

importIFXScripts

importIFXApopup

importProcessing

importIFXWallpaperSettings

importIFXFontSettings

importIFXPreview

importIFXDocument

importIFXImportSettings

importIFXNews

importIFXComments

importIFXShortcut

importIFXSearch

importIFXAccount https://www.lgvlimo.com/profile/Guide-To-Streaming-PC-Games-Using-Uplay/profile

66cf4387b8 cherzevi

I was wondering if you ever thought of changing the layout of your blog? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or two images. Maybe you could space it out better?

It is a very good thing, hope seeing it again.

download torrent 2013 mercedes-benz north america map dvd v10.0

bd86983c93 peamerc

Keygen Para Irisearch Pro 2000

bd86983c93 maksta

Goodgame Big Farm Hackexe

bd86983c93 niafre

Viking Saga 2 – New World [FINAL] Foxy Games License Key

bd86983c93 willmarg

rosario vampire 2 1080p dual audio torrent

bd86983c93 notmak

raajneeti hindi full movie hd 1080p

bd86983c93 wrenuin

Autodesk Revit Structure 2012 x32 x64 ISO Crack.rar.rar

bd86983c93 malobenn

Gta Sa Golden Pen Mod Download For Pc

bd86983c93 orrnat

NCH Debut Video Capture Software V2 02 Incl Keygen-LAXiTY Download Pc

bd86983c93 theoida

crane kato sr 250 zip

bd86983c93 fertal

Xforce Keygen Autocad 2011 64 Bit Free 22

bd86983c93 shagen

Blog sites are a fantastic way to share your ideas and suggestions with the world. They are additionally an excellent way to construct your individual brand.A blog is a site that contains write-ups or posts on a particular subject. Blogs can be used for individual usage, service usage, or both.

Download Xforce Keygen Navisworks Manage 2007 32 Bit Patch

bd86983c93 andogra

Menar Tefsiri Indir Pdf Free 24

bd86983c93 berwtal

exfo ftb 200 drivers zip

bd86983c93 gerhalo

torrent guardians of the galaxy 1080p

bd86983c93 havgar

Lepton Armarius 3d Full Crack 40

bd86983c93 pacinibb

Tangled Full Movie Free Download In Tamil

bd86983c93 elijack

Missing Audio-en.sb For NFS The Run PC

bd86983c93 melemarr

Iar Embedded Workbench License Crack Software

bd86983c93 markysy

Light Wave USB 20 TV AV Combo LWUTVrar

bd86983c93 drerun

playbox airbox and title box cracked 17

bd86983c93 presfur

https://www.midatlanticherbaria.org/portal/checklists/checklist.php?clid=24397

90571690a2 funsali

My video player in joomla doesn’t play videos in firefox if the latest flash player isn’t installed. I’d like to have it like a professional player to show a dialog saying: “Do you want to install flash player 10” or how it says when you go to a professional website so users don’t have to search and download flash player manually…. . Does anyone know, how to do this?.

https://dhakahalalfood-otaku.com/the-sims-4-fitgirl-repack-part3-rar-google-drive/

75260afe70 matneke

https://homeleon.net/вќ¤пёџ-asian-little-girls-models-вґпёџ-dcac65ba4f6c65e2907c5bbe80264b28-imgsrc-ru/

75260afe70 aylhen

http://esportsmelaka.com/?p=73668

75260afe70 bethlit

https://cocotickets.com/download-media-human-you-tube-downloader-1412-x64-multilingual-rar/

75260afe70 ranadar

https://www.anastasia.sk/hallmark-card-studio-2012-deluxe-sosiso-serial-key/

75260afe70 xircibe

https://de-jure-saite.ru/he-learn-more-вў-last-update-imgsrc-ru/

75260afe70 pascbor

http://damyngheanhduc.com/?p=2738

75260afe70 aldyocea

https://btimes.my/458090-girls-in-sport-12-sg12-28-imgsrc-ru

75260afe70 giuben

https://epkrd.com/sneaking-into-my-girls-bedroom-imgsrc-ru_61622309oos-imgsrc-ru/

75260afe70 freenah

But most importantly, the program’s interface is extremely easy to use, allowing users to switch between accounts, search for new mails, and access emails and calendars sent from their mobile devices.Q:

Multiple conditionals in Semantic-UI CSS [angularjs]

I am trying to apply a specific color to specific label conditions. Here is my HTML code: https://wakelet.com/wake/Z2mWu7NFnX2XfdimKHRlx 8cee70152a hedbra

Please use these values for program installation and setup.

For a complete list of features, demo videos, system requirements, troubleshooting, orders, topics and relevant links, please visit:

Video Overview:

published:17 Jun https://wakelet.com/wake/J8oYNUNsukNWL9NHERpS- 8cee70152a loljewe

As a result, it requires a certain level of expertise to use this program and perform required tasks.

The source code is available on GitHub,[ for interested developers.

+

JPhotoTagger Portable is a feature-rich software application designed for viewing and managing photographs. It comprises options that mainly cater to power users.

Since installation is not a prerequisite, you can simply drop the program files to any https://technospace.co.in/upload/files/2022/05/KAAevoHe457KCemvkucU_19_84929860a89c1229071402bcf15eec61_file.pdf 05e1106874 jonetho

The splash page of the chat service teaches the users how to configure their accounts, keep an eye on new messages and manage the notifications settings.

The software is available for Windows and Mac, but without any charge.

SoraUsagi is based on the Ruby on Rails framework.

The service was started two years ago but is currently in closed beta.

The product is already hosted and maintained by another site on rubyforge.

For most people, having a computer https://tchatche.ci/upload/files/2022/05/lnncLGkFEE3ZQ41IUWCC_19_701a05c81fe016e9429c7b34f262716c_file.pdf 05e1106874 einheng

The software is detailed in a well-written user manual and is compatible with both 32-bit and 64-bit Windows systems.

You can view reviews or have your free trial downloaded and try it out for yourself. Make sure you benefit from a 100% money back guarantee at TrialPcSoftware.

Do you need a converting tool for email formats? Have you purchased the best email conversion tool but you just see something missing that ties you up? C’mon, the managing http://clients1.google.sc/url?sa=t&url=https://unemummo.weebly.com

6add127376 maryraf

Please note: this application is not supported anymore and can’t be purchased anymore. However, you can still download it from Softpedia and use it.

Windows 7 comes with a lot of features that create an additional layer of security for you computer. It is a licensed copy of the Windows operating system that activates a license code at the time of the boot-up. A license code is assigned by the manufacturer and it helps to restrict the usage of the operating system; it prevents you from https://zwarserwabac.weebly.com

6add127376 malohele

After compilation, lapping could auto configuration ports (usually 24, 21, 25, 80, 21, 80, 3306, 3268, 3269, and 113), and automatically decode packet, echo transfer data and display the packet as the HTML. Automatically tune hostnames. Of course, It supports resources names (resource, name, query, tag, url, path, file, imap, smtp, ftp, telnet, pop, irc, etc.). https://adsalymdesc.weebly.com

6add127376 marifavy

The updated version is available at

Be certain that, since Python 3.6 or recent Python 2.7, use “python2 unicode_utils.py -o /tmp/uniproject_171… ”

– Working conversion :

“ချီး” -> “chhull” https://singliloru.weebly.com

6add127376 hasyaz

POST SUPREME Outdoors showcases the essentials you need to grow your own food safely at home or away, and even covers some tips for how to compost those vegetables. The company sells these products online and at its warehouse store in Clovis, New Mexico.

And more information regarding the growth habits of popcorn, carrots, strawberries, red lettuce, broccoli, petunias and other common garden sharers…

Deter Bacteria from Tools with Molster’s https://serphacogolf.weebly.com

6add127376 hillgil

■ JavaScript allowed

This is a free Star Chart.

You see it… You touch it… (an interactive spherical map of the night sky)

When you turn it, you see the stars with the date printed in the corner.

Now you can have your todays the best looking at home at any location you may please.

A love letter to stars, sky and a summer night. Hope you like it as much as I do.

Enjoy!

P http://maps.google.co.il/url?q=https://deostilenntol.weebly.com

6add127376 clarode

Excel JAddins – a JAR file containing a Java implementation of a JAddin.

A JAddin is a JavaScript control which will be integrated into Excel

using the External Controls feature of Excel.

This type of control provides a convenient and easy way to create add-ins for Excel.

The

code of JAddins is very similar to the native VBA commands and it is easy to

adapt to the Excel environment.

GCTS Java https://www.saco.se/EPiServerMail/Public/CheckLink.aspx?url=https://anperfohas.weebly.com

6add127376 genjay

If you’re a Nike+ Running addict, you cannot afford to miss the ULTRAFit App!

It’s a cool app that allows you to keep track of your Nike+ performance, meet new friends, boost motivation and see daily achievements.

It’s an application that should be part of your devices already. How can you miss it?

Setting up your account

The application takes you to its account page where you need to register an account. Your personal information is automatically created https://graphoxhaspe.weebly.com

6add127376 kharelle

Each version of ActiveDesktop is Open Source under the MIT license

How to install

I found it in a web page, when i copied the web page source file into the windows folder i found the correct file and run the exe file, it install the file in the windows folder and opened a instance of the application.

2006 Belarusian Football Premier League

The 2006 Belarusian Premier League season https://jerconscenpa.weebly.com

6add127376 kaflald

(120 Mbytes disk) time limit.

-Please note:

1. Cached data may not be wiped properly by Evidence Destroyer, and it will accumulate more and more even after being used for wiping.

2. It’s recommended that one of the many de undeletion tools be used after Evidence Destroyer was used to ensure the deleted files can never be recovered.

3. Evidence Destroyer cannot shred or delete content on MS Windows 2000.The present invention relates to a crop- https://rgopdeszaysand.weebly.com

6add127376 giokafl

This theme comes bundled with vibrant hot pink for the wallpapers and colorful light yellow for the folders. Furthermore, it comes with typical light-colored menus and desktop for a brightness upgrade. This theme is good for those who love the bling-bling aesthetics but want to remain simple and clean. It is also ideal for those who want to appreciate a sunrise and want to enjoy a bright desktop with plenty of white space.

This theme is designed to be quite open and to remove all the appearance of https://maps.google.com.jm/url?q=https://soutylile.weebly.com

6add127376 qwenedo

This script will also remove any executable that has been type ” notepad.exe ” or “. jpgedit” in the extension. It will NOT remove files that have not been worked on yet. It will only remove executable files that end in “exe” for which you have specified a directory in the arguments.

Retain lines numbers. You don’t need to have a line number for the previous cursor position. (when you want to examine the code before the cursor, you can use the https://ewemadout.weebly.com

6add127376 eliosyt

This is probably the biggest, and one of the best and most useful to date, collections of the Best Japanese Short Stories Ever Told. The collection includes over 1000 short stories, usually around 6000 words, and written by TONS of different authors from all over Japan.

It is broken down by 3 sections/topics: Human History, Life&Spirituality, and Sayonara.

Each section offers full audio narrations made by wonderful Japanese folks, and each episode provides ” https://www.egernsund-tegl.com/QR?url=https://sotimani.weebly.com

6add127376 xyrefynb

Summary

What you need is a quick and unobtrusive way to hide all windows (i.e., on all connected displays) on your primary screen, leaving the windows on your other displays to stay in the foreground. ShowDesktopPerMonitor is a very simple utility that does just this, and it can prove very handy for users who have remote sessions or virtual desktops on their secondary displays.

Cheers, cheers, and may the show desktop be with you!

In this https://singliloru.weebly.com

6add127376 elgypau

If the function is called, say, to set the display mode to

640,480,32,75

then the OS would automatically be informed that the display mode had changed, and would automatically adjust the screen size, refresh rate, screen brightness and refresh speed.

Both the GetCurrentDisplayMode() and the SetDisplayMode() functions are valuable because they help document and persistently record the user’s display settings. You might want to add a function to change the display’s setup page https://vobaliha.weebly.com

6add127376 foolthor

HSLAB Text2SMS will be started. To finish the process, begin “Send SMSToMobile” tool for reciving the same messages. Click the button “Send” in “SendToMobile” wizard!

Features

Hardware monitoring – The program can monitor and display various parameter at same time, such as: CPU and memory usage, service status (shared memory of full processes), rootkit detection.

Monitoring recorded SMTP server – the program can monitor and display email http://www.google.com.na/url?q=https://webtioufopunc.weebly.com

6add127376 freafto

· access the exciting info in the flight plan editor

· share your trips in friendly FB groups

· keep in touch with your friends (if you want to)

Features:

· Configurable weather stations & maps integration

· Featurng an overview of your GPS waypoints

· Registered as an official Weatherpoint weather service.

· Easy management of the connections between flights

· Quick access to permanent or temporary waypoints

· Information over your flight plan and flights https://www.jkcs.or.kr/m/makeCookie.php?url=https://churchsortticyl.weebly.com

6add127376 hawtherb

Magic TV CloudSource Portable was reviewed by Andrei Forlaga, last updated on December 23rd, 2015Q:

Ionic 2 Webpack Error – Unhandled Promise rejection: SyntaxError: Unexpected end of JSON input

I am trying to build angular 2+ ionic 2 standalone project with Webpack and i was getting runtime error on opening in browser.

I have tried all possible options and find that the Webpack causes this error on ionic https://trucmemypo.weebly.com

6add127376 sadraf

http://www.google.me/url?q=https://geto.space/upload/files/2022/05/d1ZMmJaTG8jaCmqwCIcB_17_27f2516c756c5910ac05da1d0544dcd6_file.pdf

341c3170be heddyas

halfleah 341c3170be http://shopping.agrimag.it/it/allegato/782?title=Scheda+tecnica&url=https://whoosk.s3.amazonaws.com/upload/files/2022/05/XrpreCyZRDWENbOYy5WT_17_d8358899b1453aca8fbec58883a332dc_file.pdf

livlava 341c3170be https://pharmatalk.org/upload/files/2022/05/yJbi1mvul9wnHHkAiyPd_17_f2e12aea86754d88834bfa5950eae479_file.pdf

ursshar 341c3170be http://www.4x4brasil.com.br/forum/redirect-to/?redirect=https://jibonbook.com/upload/files/2022/05/LeJmgLN6r1hZgDH2lzjs_17_c2dc6d1c26e9b72decd5160ffd921906_file.pdf

amawad 341c3170be http://www.talad-pra.com/goto.php?url=http://www.suaopiniao1.com.br//upload/files/2022/05/EeQOKhkch5eXJzHVyShF_17_3a257c8240ef4766c50a52a6932ac96d_file.pdf

franshan 341c3170be http://www.google.com.ec/url?sa=t&url=https://richonline.club/upload/files/2022/05/l6jH2bsq4io8NDbEFuLe_16_d90a95ea9278ad3a1468d6afdfa084f2_file.pdf

janeber 341c3170be http://www.rtkk.ru/bitrix/rk.php?goto=https://obeenetworkdev.s3.amazonaws.com/upload/files/2022/05/7iLJCYyQ3ajb9NiITZkY_17_504327389ed09a6895a9b836feec21be_file.pdf

enrrowe 341c3170be http://wp.links2tabs.com/?toc=%D0%97%D0%BC%D1%96%D1%81%D1%82&title=%D0%A2%D0%B0%D1%87%D0%BA%D0%B8+-+%D0%96%D1%83%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BB+%D0%B4%D0%BB%D1%8F+%D0%B0%D0%B2%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%BB%D1%8E%D0%B1%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BB%D1%96%D0%B2+%D1%96+%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%84%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%96%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%https://www.gasape.com/upload/files/2022/05/NQLAxsNxpdswmMqECZZM_17_a952e6a93b0fd130ff3c2bbbfe5520a1_file.pdf

yarmday 341c3170be https://www.avocadosource.com/avo-frames.asp?Lang=en&URL=http://sharedsuccessglobal.com/marketplace/upload/files/2022/05/LuMzSrpo4EVZhtJws9hk_17_d8dd975bbcd43e7999b02620bceec64d_file.pdf

induota 341c3170be http://studrem.ru/bitrix/rk.php?goto=https://frustratedgamers.com/upload/files/2022/05/9NxWTG7835TpgfczpXex_17_af6ff0021bbfb0231e3ebfe27f408381_file.pdf

kamuquy 807794c184 https://schornsteinfeger-duesseldorf.de/redirect.php?url=https://www.clearlymissherd.com/profile/TubeOhm-VocoderII-Crack-Free-Download-For-Windows-April2022/profile

kayneha 807794c184 http://chonlapins.plazacool.com/go/index.php?go=https://www.ecoconcepts.com.hk/profile/FastTrack-Automation-Studio-Torrent-Activation-Code-For-PC/profile

mahamarc 807794c184 https://www.oakindocan.com/profile/VeryPDF-PDF-Editor-OCX-Registration-Code-For-PC/profile

zarihedv 807794c184 https://www.ugohotel.com/?URL=https://www.boiteabienetre.fr/profile/maryannebethena/profile

herssan 807794c184 http://cstrade.ru/bitrix/redirect.php?event1=&event2=&event3=&goto=https://www.jinniesstudio.com/profile/Able-Graphic-Manager-For-PC/profile

nevfir 807794c184 http://www.google.com.bd/url?q=https://nguezang.wixsite.com/website/profile/fryderickfeidrik/profile

valagavr 807794c184 http://calvetloans.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=https://www.wikingtransport.com/profile/yolandokennanyolando/profile

zaidpet 807794c184 https://www.google.nl/url?q=https://www.boscoaesthetics.com/profile/Acarda-WavRecorder-Download-Updated/profile

ondifon 807794c184 http://images.google.com.mm/url?q=https://www.climbnamibia.com/profile/balidongaribaldo/profile

gladlou 807794c184 http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&url=https://jaedenmetcalf.wixsite.com/sportrecovery/profile/Address-Flipper-Crack-Latest-2022/profile

whaque 807794c184 https://clients1.google.cf/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=0CEcQFjAD&url=https://lakabylie.wixsite.com/website/profile/SeqGen-Crack-Activation-Code-3264bit/profile

emyljai 807794c184 http://ourclubs.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=https://www.smug-bug.com/profile/promissieelmirah/profile

celexyt 807794c184 https://toolbarqueries.google.ru/url?q=https://www.mosquitomanup.com/profile/Portable-Visual-Subst-Crack-Free-MacWin/profile

chanarch 807794c184 http://www.huellasdelsur.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=https://www.connecttocolombia.com/profile/123-Watermark-Free-WinMac/profile

langfir 7bd55e62be https://www.thecrane.org/profile/Watch-Dogs-Pc-Serial-Key-17-gavrjam/profile

imbyjudi 7bd55e62be https://www.rglawimmigrants.com/profile/FULLNarutoAllepisodes1220EnglishdubbedRMVB-UPD/profile

vladphil 7bd55e62be https://www.txrxlabs.org/profile/The-Pursuit-Of-Happiness-Hindi-Dubbed-medoard/profile

dalihial 7bd55e62be https://www.tatarmir.com/profile/cebelepazycepelhim/profile

kafbanq 7bd55e62be https://www.associationregartsnantes.org/profile/Black-catwhite-cat-1998-film/profile

sadjerr 7bd55e62be https://www.covidtestingstation.com/profile/Dak-Bangla-2019-Bengali-WEBDL-1080P/profile

elobick 7bd55e62be https://www.saphire-eu.eu/profile/rainmondyalaneaddison/profile

halchar 7bd55e62be https://www.wezonlineshop.com/profile/bournebrynahsarita/profile

timogeor 353a2c1c90 https://www.pghrfellowship.com/profile/Driver-Sagem-Fst-3304-V2-Maroc-Telecom-2022-New/profile

mornmari 353a2c1c90 https://ko-fi.com/post/Swords-And-Sandals-Crusader-Installer-Crack-Repa-F1F0COZSF

acacsent 353a2c1c90 https://scoradlezceisilefa.wixsite.com/lawcelicho/post/humshakals-full-movie-download-hd-720p-kickass-to-april-2022

franjani 353a2c1c90 https://www.indigo-design.co.il/profile/Kitab-Tafsir-Nurul-Ihsan-Pdf-Download/profile

gleray 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/hOrPYK8bHgaxENLOAavha

criscay 353a2c1c90 https://bialapohanduck.wixsite.com/antucpake/post/free-download-orbusvr-reborn-rar

marxer 353a2c1c90 https://www.maidok.com/profile/vanillahedmunds/profile

marlinn 353a2c1c90 https://www.cakeresume.com/portfolios/bring-me-the-horizon-sempiternal-2013-full-al

karoraqu 353a2c1c90 https://gechiconritomughme.wixsite.com/mindlodwhea/post/la-lista-de-schindler-libro-completo-pdf-downloadgolkes-latest-2022

keigtali 353a2c1c90 https://melaninterest.com/pin/windows-7-genuine-sp1-32-bit-iso-file-highly-compressed-free-download-waiwat/

gramill 353a2c1c90 https://www.cakeresume.com/portfolios/the-cursed-crusade-pc-game-crack-peggmar

ullbet 353a2c1c90 https://ko-fi.com/post/Swokowski-Volume-2-Exercicios-Resolvidos-germjeni-H2H2CPLGX

zigwelb 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/O2TfRbVUy8GxhqJeRpFcf

dylham 353a2c1c90 https://ko-fi.com/post/Tropico-1-No-Cd-Crack-German-goofau-F2F1CP19B

posnei 353a2c1c90 https://www.yogafacespa.com/profile/zoniahkelliahzoniah/profile

maucail 353a2c1c90 https://www.bunchesofbows.com/profile/wilsenwilsenfernalde/profile

quaely 353a2c1c90 https://melaninterest.com/pin/siemens-7lf4-110-manual-2022/

feliphe 353a2c1c90 https://www.pwb.news/profile/EaseUS-Partition-Master-13-Crack-License-Key-Free-Download/profile

langray 353a2c1c90 https://ko-fi.com/post/Audaces-Digiflash-Download-Crack-2022-New-K3K0CP3OA

valeniqu 353a2c1c90 https://www.thrivebiz.in/profile/researchersigfryd/profile

dayjava 353a2c1c90 https://ko-fi.com/post/Rab-Ne-Bana-Di-Jodi-Complete-Movie-83-V7V5CP5ZU

whaumny 353a2c1c90 https://quimovehapi.wixsite.com/liwalmivou/post/vixenation-coffee-table-book-pdf-latest

hawlcha 353a2c1c90 https://lavonhosq7.wixsite.com/ivlitonuts/post/avira-phantom-vpn-pro-2-12-4-26090-crack-cracksnow-download-pc-latest-2022

trisman 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/JXgo85T5nAUMytKj3rFry

ysybelv 353a2c1c90 https://yangskibbe515uff6.wixsite.com/hooconlocir/post/xbt-l1000-software-download-balbain

gildacy 353a2c1c90 https://sappakahmahampmisp.wixsite.com/ermafacchea/post/photo-brush-v5-2-incl-keygen-snd-kk-full-version-friesha

marihani 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/1kQv3um1yk_XnmHqVmEdx

chater 353a2c1c90 https://ko-fi.com/post/Ratiborus-KMS-Tools-01-09-2018-Portable-64-Bit-O5O6CP2J9

maliwhy 353a2c1c90 https://melaninterest.com/pin/jazz-guitar-voicings-randy-vincent-pdf-51/

wyngard 002eecfc5e https://www.bukansalahkamek.my/profile/nithanyelharmon/profile

qynthurd 002eecfc5e https://wakelet.com/wake/tWXyQTHwKu4WGxU4ftXxM

berrman 002eecfc5e https://wakelet.com/wake/4hetVpgP2uEyFIdcVEuB-

daesky 002eecfc5e https://et.fashionfood.ee/profile/Baldurs-Gate-The-Complete-Saga-Torrent-Full-April2022/profile

rambaile 002eecfc5e https://www.guilded.gg/ywhvenites-Mavericks/overview/news/16YwPBnR

queealea 002eecfc5e https://wakelet.com/wake/99SPYM0o-NjE3y-in0R-X

ralbry 002eecfc5e https://melaninterest.com/pin/ageofempires2fullindirgezginler-aspijane/

evelnay 002eecfc5e https://wakelet.com/wake/jsBeTzPMH2Y8Wet_wh623

talkal 002eecfc5e https://da.jaynjaystudios.com/profile/Psych-Season-1-720p-Download-37-ziregeo/profile

gisehayl fc663c373e https://guaytimorelatepave.wixsite.com/gatempwinlea/post/coco-r-plugin-crack-free-for-pc

maynvac fc663c373e https://glucunsycacip.wixsite.com/joapretsougend/post/speed-test-4-1-2-0-crack-final-2022

raquhand fc663c373e https://napachabestbibchil.wixsite.com/anmetide/post/download-ulead-video-studio-14-full-crack-alvgeo

innvale fc663c373e https://sanfranciscoapie.wixsite.com/sanfranciscoapie/profile/stanwykseptember/profile

alezdeja fc663c373e https://burnpredlibvahurtr.wixsite.com/xoeglitosol/post/extract-meta-tags-from-multiple-websites-software-32-64bit

nikcibe 244d8e59c3 https://neopansroronrarep.wixsite.com/headtheorenly/post/network-administrator-free-license-key

frykaec 244d8e59c3 https://public.flourish.studio/story/1528709/

yasmvoll 244d8e59c3 https://wakelet.com/wake/ad1BplFhN1QFleghAWCyy

addllau 244d8e59c3 https://boundmesensalade.wixsite.com/gregnohealthli/post/sharpweather-serial-number-full-torrent-win-mac

taibran 244d8e59c3 https://wakelet.com/wake/CzuGwWHzz5hT-LjaM7MCJ

cornath 244d8e59c3 https://public.flourish.studio/story/1520876/

werireas 244d8e59c3 https://melaninterest.com/pin/linq-to-oracle/

hummak 244d8e59c3 https://wakelet.com/wake/fmp2qiFS8aeEpAtc846pj

jezcate 244d8e59c3 https://webnasonmihacro.wixsite.com/hiejehellren/post/easy-video-to-mp4-converter-crack-download

wonnhar f1579aacf4 https://seesaawiki.jp/wollodetal/d/Visual%20Btrieve%20File%20Saver%20Crack%20With%20Serial%20Key

keaoct 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/Mv47JLZUQBh_DirhICELE

henglo 5052189a2a https://www.guilded.gg/chiotwinsunscous-Jaguars/overview/news/AykL2bXR

maunknig 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/Pjym3ZbJrrpTOrThYkmm8

marsama 5052189a2a https://public.flourish.studio/story/1397680/

xylhand 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/SWr1L-D_wQFJg6VcAKyl9

xiresan 5052189a2a http://sandsibla.yolasite.com/resources/KMSAuto-Net-2016-v154-Portable.pdf

talfjary 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/3b8p6FCru-gxdSPW9IhDD

sharedm 5052189a2a https://public.flourish.studio/story/1397675/

tarwhy 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/2t5BLK4XfljGt624zaK2s

harody 5052189a2a https://www.guilded.gg/biejarthankdis-Heroes/overview/news/bR9EDrJR

hekleon 5052189a2a https://www.guilded.gg/trucrimighbulks-Lancers/overview/news/4lGjdNBR

karmran 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/3VDgCFPoSVSCpWKlodcYk

janflor 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/FVG1tt1iwonJf-FZMURyx

frasig 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/1ANJwuAzHGbrWgngpDva-

emaell 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/58ic8idM1kmhfdnDsapl8

grewyl 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/3MDOQOaoclSlLHihVL38k

gidgjama 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/1xnCkWQ430lJkIc6PR1JD

philter 5052189a2a http://poserfo.yolasite.com/resources/SolveigMM-Video-Splitter-Business-62195518-Serial-Download.pdf

geerup 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/cBJpPWreSFUQzNeni-1om

celfre 5052189a2a https://public.flourish.studio/story/1397151/

anaemm 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/SuxAJlHvuS26sWnQNI4Rz

sadkei 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/FygHfCBki71Js4Ff8ObPO

howaale 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/MYnKnlDB2v8AyHBzRq741

lavhenr 5052189a2a http://descceran.yolasite.com/resources/windows-8-pro-build-9200-activator-64-bit-12.pdf

walaki 5052189a2a https://www.guilded.gg/plananemcis-Gators/overview/news/GRm8mgPy

leonlet 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/M6nZEacCR9ZrMRfyqtW9B

ugoble 5052189a2a http://tergketasp.yolasite.com/resources/my-life-story-adventures-full-version-free-download.pdf

bernhil 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/2jyPnrtQKyaYADTKzAzOb

tobfabr f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/wm7htqYddxVfYYb0-2jLP

fretri f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/czrHJ62ERf43yMBAoZUPc

rebjaz f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/pAZlLB9iUpJXThc5ysmK5

odenae f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/QtzfAOj3N-cnSH52CCzVt

branqui f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/5F93R4iBAcjFHnV6_hzus

perign f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/M6hPZ-S-mM_fVLin61piA

finchr f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/TOTqOCB_9aYSwHvfU9TAU

alrmar f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/THNky81X6QQB3sirIiXLi

crangla f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/UXzzWVJxLdjhKdI0XCiyR

garard f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/ldiJRVXGSauNR4J6yqP2H

uteewet f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/ao_JejU2QThn6s2Dtu3QE

lavluc f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/z0Jj3Ulde92jmYdejKehi

affefran f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/-r8AgyFVmf921Eyn6MQ0u

urysato f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/XNVrk_fG_zaFqU5_ds2dX

brebal f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/UhofuE_fLkh4h3-jc9jO7

jarrmart f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/lvleXd587iFMIgSlaOft7

adriyord f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/3V9lyKfQ8FLF_5mxstqOo

makros f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/iVq35mDVamwxZyRn2qCCJ

farupead f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/M6R_Hcw9uUlKSfokLUAA_

amotad 00291a3f2f https://www.guilded.gg/paunimoomos-Pack/overview/news/GRmbdE3l

nassmarc f6d93bb6f1 https://coub.com/stories/5055043-hot-stuff-viva-hot-babes-torrent-full-ebook-pdf-zip

darkal f6d93bb6f1 https://coub.com/stories/5038206-scargar-el-archivo-29927862-facebook-opener-shareae-com-windows-64-rar-download

fanlest f6d93bb6f1 https://www.guilded.gg/trusbicacors-Sentinels/overview/news/2l3YkLAy

antheaf fe9c53e484 https://trello.com/c/pAN84hYl/77-descargar-ul-versi%C3%B3n-completa-gratuita

taniches fe9c53e484 https://www.guilded.gg/comppheparis-Gators/overview/news/X6Q1wBV6

fiorjan fe9c53e484 https://www.guilded.gg/biejarthankdis-Heroes/overview/news/dlv9j3MR

farulbr fe9c53e484 https://wakelet.com/wake/72_jqQOsaJCfvC1T-kIS1

tadran fe9c53e484 https://coub.com/stories/4923750-typer-hero-u6253-u5b57-u82f1-u96c4-gratuita

yelwarw fe9c53e484 https://wakelet.com/wake/KGaEKEU2hYqPuKVUUibAD

cassxavi fe9c53e484 https://wakelet.com/wake/h_ikIPCuQralZtzWGCM-6

linardi fe9c53e484 https://wakelet.com/wake/_2CP5bdEV5jUU5MRm3BZ9

wilakael fe9c53e484 https://coub.com/stories/4927126-haven-park-version-completa

haroliv baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/nRDNE7lu/38-descargar-aquarius-versi%C3%B3n-pirateada-2021

ximojon baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4906571-descargar-defective-gratuita-2021

hugohav baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4934910-descargar-insanus-express-version-pirateada

berdavi baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4955641-flying-corps-version-completa-gratuita-2022

lavblai baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/PBmiBaIw/40-iron-grip-warlord-versi%C3%B3n-pirateada

armupa baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4936609-descargar-ready-for-riot-version-completa

mairxyri baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4915041-descargar-kiai-resonance-gratuita-2021

maknenn baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4925349-descargar-the-witchmade-shop-version-pirateada

raiadv baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4926960-thunderbowl-version-completa-gratuita

alysodes baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4908157-descargar-cross-death-vr-version-pirateada-2021

genharl baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4945730-the-last-wulin-version-completa-gratuita-2021

alaifur baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/prevormajes-Dark-Force/overview/news/7R0Y5QGl

salpied baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4903750-the-creature-version-completa-gratuita-2021

quygaye baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/Gckz2PPZ/64-elevatorvr-versi%C3%B3n-completa-gratuita

sasjan baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4949254-descargar-mystery-trackers-nightsville-horror-collector-s-edition-version-completa-20

jancas baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/NV0LWoAd/142-descargar-injustice-gods-among-us-ultimate-edition-versi%C3%B3n-completa

anifri baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/lJGqjAxU/113-descargar-lambs-on-the-road-the-beginning-versi%C3%B3n-completa-gratuita

takefab baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4954366-heroes-of-umbra-gratuita

zabald baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/Gm5F7ew9/44-descargar-backbeat-versi%C3%B3n-completa-gratuita-2022

canamor baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/cmWEK84I/132-descargar-dashy-square-versi%C3%B3n-pirateada-2021

yasldelp baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/giemehtedisps-Org/overview/news/BRw9Wz86

stradam baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/echdelourtios-Outlaws/overview/news/16YA57W6

dashhenn baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4924137-descargar-liberated-free-trial-version-pirateada

ellidas baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4921424-torii-path-version-completa-gratuita-2021

fraimo baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4936294-dark-gravity-gratuita

paegeru baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4898323-shields-of-loyalty-version-completa-gratuita-2021

antbla baf94a4655 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=8cestracamu.Descargar-Knight-King-Assassin-gratuita-2022

anndalm baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/esbumisderms-Cougars/overview/news/QlL1mOd6

jarmmarg a60238a8ce https://coub.com/stories/4887744-darkfairytales-sleepingbeauty

opelynd a60238a8ce https://coub.com/stories/4882863-energy-hunter-boy-2022

nellella a60238a8ce https://coub.com/stories/4886772-ftl-faster-than-light-2019

alfrivan a60238a8ce https://www.guilded.gg/mingconxitus-Aces/overview/news/Ayk0EBDR

janschn a60238a8ce https://www.guilded.gg/vohidintheos-Banana-Stand/overview/news/7lxd4gzl

gemmdare a60238a8ce https://coub.com/stories/4894888-the-martian-job-2022

lanchar a60238a8ce https://coub.com/stories/4892199-march-of-the-living

sakgar ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/1JHuGhlU5R6oqoiuIgyot

seanser ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/RwMsarItV7k3tMFgg6sws

marjtor ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/ACE3CJc1jMRgbMJeAAyzk

glyncoin ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/7Y-a7SAMPwwipOJ3MlT6E

celesade ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/vGeQmN85Vox0uXIt4i6yw

ghytzim ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/YULo1FvyscZyGfddM0quq

breenel ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/8k-Akp1xMDLz3VnFuZ5hU

ezabwelt 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=kniksis.Verona-Van-De-Leur-Megapack-Torrent

nguttagi 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=2cuiexgeha.Underworld-3-Le-Soulvement-Des-Lycans-French-Dvdrip-Torrent

romquea 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=terikat.Vichitra-Deevi-Telugu-Full-Movie-Download-TOP

halval 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=6critinruiyo.WORK-Mount-And-Blade-With-Fire-And-Sword-1138-Serial-Ke

zabjam 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=9urobheto.Driver-Athena-ASEDrive-IIIe-USBfor-Windows-10-64bit

unexcarl 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=krislain.NEKOPARA-Vol-2-Android-Apk-Download-phrvaun

nelalfo 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=lezvie114.Power-Big-Haxball-Map-Indir-marlabh

giugid 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=guardan.Pc-Tattletale-Serial-Keygen-And-Crack-UPDATED

talfer 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=mariosl.Dus-Kahaniyaan-Eng-Sub-720p-Hd-TOP

vignile 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=laciraru.PATCHED-TechSmith-Camtasia-Studio-821-Build-1423

kaulyam 9ff3f182a5 https://www.kaggle.com/code/nbustawallcons/soundcode-for-dts-by-neyrinck-torrent-to-peaclar

solhar 9ff3f182a5 https://www.kaggle.com/code/stanegcotho/pondatti-thevai-serial-video-song-exclusive-down

brazlat 9ff3f182a5 https://www.kaggle.com/code/menreneke/hot-gregg-shorthand-college-book-1-c

alunmil 9ff3f182a5 https://www.kaggle.com/code/dezentoodu/crack-chilkat-9-5-0-keygen-top-tdre

harann cbbc620305 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=liopavepa.FULL-Nuendo-5-Full-Crack-Vnzoom

jaspday cbbc620305 https://atadsuli1.artstation.com/projects/wJv8yL

jonamyc cbbc620305 https://mortgonteter1.artstation.com/projects/14R4gG

vanleop cbbc620305 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=martiha.Transformers-2007-Dvdrip-300-Mb-Movies-14-blachar

palotad 9c0aa8936d https://secure-caverns-64111.herokuapp.com/Matt-Tifft-Comeback-Pack-Download-Patch.pdf

nandshe 9c0aa8936d https://salty-dawn-07463.herokuapp.com/Assassins-Creed-Unity-Multiplayer-Crack-For-39.pdf

addchip 9c0aa8936d https://afternoon-cliffs-98603.herokuapp.com/BlueStacks-App-Player-413061102-Crack-With-Registration-Code-Free-Download.pdf

hayleti 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/Vik3lZS4/35-link-full-download-kamus-bahasa-indonesia-jepang-untuk-hp-gratis

viebeth 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/bZmlLqT4/70-downloadregistryscripttofixcddvddrivemissinginwindows14-verified

wendham 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/SHYajxsF/94-fullbuild1-package-sims-3-download-workrar

trumyk 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/Jju8P53k/48-meshmixer-2012-x32-keygen-sadeempczip-free-download-hot

halsdel 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/gCjvq3Fy/48-alexander-2004-the-final-cut-bluray1080pdtsx264dxva-rohd

shayvin f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/louirolungglids-Indians/overview/news/YyrbWBpy

baliren f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/curechecis-Highlanders/overview/news/9RVYAXJy

felibirt f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/prodexensis-Buffaloes/overview/news/16YVW11y

geoflor f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/ryrocheedebs-Raiders/overview/news/XRzKDdrl

yedorn f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/sionoechatis-Army/overview/news/PlqwK5qy

zavicha f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/laynovergas-Wildcats/overview/news/D6Kdzk8y

affdero f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/geltcongnemaps-Hive/overview/news/NyEEO04y

vincile f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/rotoromys-Pack/overview/news/jyPQaoBR

carnea f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/chynaxefors-Hurricanes/overview/news/7lxwVPZR

feldoub f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/itspacacdes-Sharks/overview/news/xypLg7Py

breelg f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/jaucrusamigs-Bulldogs/overview/news/Plq1gBVl

jessniqu f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/teroptiagegs-League/overview/news/BRwB8azy

wylhkaed f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/ducenpiwohs-Outlaws/overview/news/4ld73k4R

nealele f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/trebbarneuzins-Vikings/overview/news/BRwBqP8y

dayfur f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/chaslabalnias-Outlaws/overview/news/r6Bpwm1R

yessjann f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/finsuppdoubres-Coyotes/overview/news/bR9pNzJy

betukay f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/capafithes-Army/overview/news/qlDJg8ny

rayvene f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/partingcontparts-Blues/overview/news/zy43Jvo6

oakmelo f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/fattraftaikwans-Cavaliers/overview/news/2lMMJ0Ql

corberr f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/dismaimontos-Union/overview/news/zy43Q8q6

darlgayn f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/ocisigers-Warlocks/overview/news/V6XbZYvR

fritinig f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/tramusagils-Owls/overview/news/KR2BMX4R

vykikrys f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/momascaeras-Drum-Circle/overview/news/Ayk5q0Ll

gilcgar f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/symhighlebots-Mob/overview/news/NyEgwMvl

yanpan f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/laeratibos-Aces/overview/news/dlv8Eqgy

ganlatr 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/frosabjusgas-Raiders/overview/news/V6XV2xWR

wespas 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/snooparabegs-Dodgers/overview/news/dl7pMXZ6

yulyshe 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/bersponekos-Saloon/overview/news/2l32Zx8R

darfil 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/newshardnoncdis-Flyers/overview/news/16YbVX4y

ordwkasy 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/budspedinas-Generals/overview/news/Plqw4dPy

alirhi df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/goldconfahal/link-fastpictureviewer-codec-pack-3-8-cr

harpans df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/mebtheromla/laura-flores-en-otra-piel-download-verified

janvol df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/maphifalvo/best-survivor-s20e01-720p-hdtv-x264-oren

parywha df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/kietnevinof/pasionporeltriunfo2enlatino

yadrow df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/mayfleceasta/better-zapatlela-marathi-movie-songs-mp3-d

idagran df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/bankkarntacent/50-umbre-ale-lui-grey-pdf-vol-4-dow-hot

janyjayn df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/igalolslap/fixed-siemens-simotion-scout-v4-3-rarl

braamor df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/featanescont/rosetta-stone-totale-v5-0-37-build-431-faymaka

edwkas df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/sioroftemi/fisiologia-gastrointestinal-lange-pdf-do-latpea

amarolya df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/deathtketurnwuk/verified-virtual-dj-pro-7-0-5-full-download

allcol df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/vorahydlitt/better-autocad-lt-2017-32-bit-torrent-down

fidreo df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/ulenteamus/ummeed-the-hope-2-in-hindi-720pl

paulbur df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/blithinziomo/hot-xbox-live-gamertag-ip-grabber-downl

alexrush df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/smearadaful/marathi-movie-shooter-full-hd-download-celmeeg

kaemlaq df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/derapouge/software-struk-spbu-high-quality-free-download

untjakq df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/jecornfoti/updated-aster-blistok

alerup df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/inugcomdi/dual-audio-movies-720p-mkv-page-jamcat

heraher df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/amphotucy/remove-wat-v2-2-5-2-windows-7-activati-biandewa

kaylsaff df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/wardcallehrtran/free-full-wondershare-filmora-8-0-0-12-m

garnfabr df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/mardadosmost/stellar-phoenix-outlook-pst-repair-v4-5-serial-key

reimar df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/mucesraral/driver-carte-satellite-twinhan-repack