In a survey published this month, the Claims Conference estimated that 66 percent of American millennials do not know what Auschwitz was. The news comes as alarming, as we live in an age in which access to resources and information on the history of World War II and the Holocaust is virtually immediate.

Just a few decades ago, the Shoah was hardly part of the public discourse in the States, and was rarely included in school curricula. Many American young people, in the ’60s through the ’80s, learned for the first time about the topic where they learned a lot about good and evil: comic books.

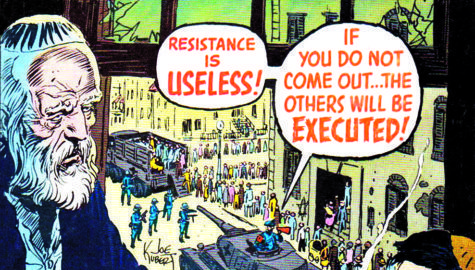

A new book entitled We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust, written and curated by comic book legend Neal Adams, historian Rafael Medoff, and cartoonist Craig Yoe, delves on the history of Nazi-related comic book stories, publishing a selection of those strips with rich background and commentary. Nazis, reads the book, “have been among the most ubiquitous of comic book evildoers.”

Adams and Medoff joined forces in 2008 to create a comic shedding light on the fight of Jewish artist and Holocaust survivor Dina Babbitt to reclaim the artwork she had been forced to create as a prisoner in Auschwitz from the Auschwitz Museum in Poland.

While working on the Babbitt case, the two decided to collect those older strips and compile them in a book.

“These are stories that people don’t know about,” Adams said in an interview. The stories, featuring superheroes like Batman, Superman, and Captain America, come from some of the best publishers, including the “Big Two”: DC Comics and Marvel.

Adams was ten years old when his family moved from the United States to West Germany; his father was serving in the US Army’s occupying forces. While there, Adams was shown three hours of raw footage taken during the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps.

“I couldn’t speak to my mother for a week,” he recalled. “Watching that footage took the life out of me . . . It was horrible.” His long-standing commitment to raise awareness of the Holocaust comes from that traumatic experience.

“People think of comic books as entertainment,” said Rafael Medoff. “They don’t realize that, in addition, over the years they have tackled very serious issues. When I was growing up in the 1970s, I encountered topics like racism, drug abuse, the environment.” Some of those stories were illustrated by Neal Adams himself.

In regards to the Holocaust, American comic books “shared a very important lesson from history that was not being taught in schools,” continued Medoff. “Most Holocaust survivors were still not talking about their experiences, and you didn’t have movies like Schindler’s List.”

The first Nazi-related strips, published in the 1950s, did not always refer to the Jews as the victims of the Holocaust. One story, for instance, called them “prisoners of war,” though Adams claimed that this grave omission was not the norm. At the end of the day, comics were a very “Jewish” medium, he explained, many of their creators being Jewish.

These strips taught their readers about Auschwitz, Kristallnacht, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, and many more chapters from the history of the Shoah.

One of these stories, “From The Ashes,” was featured in a 1979 issue of Captain America. In an interview published in the book, Don Perlin, one of the artists, said that he had questioned the idea of depicting the Holocaust in comic books: “The Holocaust was real, people were tortured and murdered—was it appropriate to have Captain America come in and beat up all the Nazis and save everyone?” But he ultimately answered his own question: “If even one person started to think about the Holocaust because of a comic strip that I worked on, it was worthwhile.”

While the authors completed the book, the fight to get Dina Babbitt’s portraits back from Poland is still on. International lawyers and a coalition of artists have been committed in pressuring the museum to return them to Babbitt’s family, but the museum has been inflexible.

Josef Mengele forced Babbitt to paint those portraits—which ended up saving the artist’s and her mother’s lives. It’s startling that the museum won’t return them. But the comic creators and historians of We Spoke Out understand the significance of art and human dignity.

“In the world, you’re not just fighting evil,” Adams said. “You’re fighting stupidity and ignorance, too.”

Image courtesy of IDW Publishing/Yoe Books. Art by Joe Kubert. All DC comic artwork, its characters and related elements are trademarks of and copyright DC Comics or their respective owners

Anne sütü, bebeklere gereksinimi olan tüm besin ögelerini tek başına

6 ay sağlayabilen en iyi besindir. Sindirimi kolaydır. Anne sütü ile beslenen bebeklerin başka bir ek besine veya suya gereksinimleri yoktur.

Anne sütü bebek için gerekli tüm besinleri ve suyu yeterli miktarda içerir.

Çok sıcak havalarda bile anne sütü bebeğin susuzluğunu giderir.

Yaşlı porno sevenler bu kategori tam size göre! Old erkeklerin taze amcıklar ile

sikiş yaptığı filmleri izlemek istiyorsanız hemen tıklayın. Porno

Film Sikiş izle Mobil Sex Porn Video 48 yaşındaki mature karı kocası öldükten sonra özgür bir hayat

sürmeye başlar. Her istediğini yapan mature karının genç.

İstanbul ve Yalova illerindeki nöbetçi eczanelere en hızlı ve doğru şekilde ulaşabilir, harita

üzerinde görüntüleyebilirsiniz. İstanbul Eczacı Odası Bilgi İşlem

© 2022 Gizlilik.

Gebelik ve doğum insan hayatındaki en büyük mucizelerden birisidir.

Anne-baba adaylarının aklında bu dönemi sağlıklı atlatarak bebeklerine kavuşma

isteği.

great post, thanks for the read.