Jews are not the only people ravaged by memory. For African Americans, it is the long arm of slavery that holds back the living. “…[m]ama told me what they all lived through, and we were supposed to pass it down like that from generation to generation so we’d never forget,” the central character of Gayl Jones’ Corregidora explains. This novel tells the truth more convincingly than many testimonials. “Always their memories, but never my own,” blues singer Ursa muses, the insistent negation of the phrase an echo of the Jewish pledge against forgetting. Here a hysterectomy proves strangely restorative: prevented from “making generations,” Ursa conceives a life that sustains more than treachery. Want becomes wanting: in singing, she expresses desire as well as loneliness.

Jews are not the only people ravaged by memory. For African Americans, it is the long arm of slavery that holds back the living. “…[m]ama told me what they all lived through, and we were supposed to pass it down like that from generation to generation so we’d never forget,” the central character of Gayl Jones’ Corregidora explains. This novel tells the truth more convincingly than many testimonials. “Always their memories, but never my own,” blues singer Ursa muses, the insistent negation of the phrase an echo of the Jewish pledge against forgetting. Here a hysterectomy proves strangely restorative: prevented from “making generations,” Ursa conceives a life that sustains more than treachery. Want becomes wanting: in singing, she expresses desire as well as loneliness.

Utopian the novel is not. If it closes on a note of ambivalent promise, Jones does not jettison the past. Still, the book argues forcefully against the blind continuance of oral history when this becomes more disabling than recuperative. Recalling hurt repeats the injury: “We got to burn out what they put in our minds, like you burn out a wound,” her mother tells Ursa. “Except we got to keep what we need to bear witness. That scar that’s left to bear witness. We got to keep it visible as our blood.” Her relatives school her to continue this painful catechism, but Ursa refuses. Burn. Wound. Scar. What are you left with? Better to cut yourself away from your roots than be strangled by them. Jones invokes surgery to literalize this principle, but other novels offer parallel admonishments. The heroine of Octavia Butler’s Kindred escapes the antebellum South though she loses her right arm in the process. The central figure in Toni Morrison’s Beloved beats back the past each day only to be haunted by its specter every evening. But eventually Sethe learns too. “This is not,” Morrison concludes, “a story to pass on.”

The pronouncement is one Jewish Americans would do well to heed. Morrison’s character sacrifices the living memory of her child for “beloved,” the word chiseled in pink granite on her murdered daughter’s gravestone. The substitution calls attention to what we already know: too well tended, the practice of grief effaces the features of those we mourn. The massive stone of the monument pulverizes the traces of particular lives. While the children and grandchildren of Holocaust victims wish away the bitterness of their unwanted legacies, the rest of us rush to take on their burden, staring fixedly at images of the death camps as our family photographs fade to sepia.

We value what is called collective memory because it plays an important role in the preservation of our cultural life. “A people’s memory is history,” the advertisement for a Carolina oral history project announces. The phrasing sounds pleasing but its equation puzzles me, for the daydream of memory and the deliberate evocation of the past we know as history share little beyond their retrospective vantage. Chronicle can be revised, rejected, reconsidered. Memory is mostly fugitive. Its transience and its impermanence account for the wistful potency of exilic story, as well as the residue of anguish that underlies our efforts to call up images of the people and places we have lost. Still, the commandment to remember holds us captive. Nobel prizewinner and Auschwitz survivor Elie Wiesel routinely invokes its persuasive power. “Your presence here,” he told a group gathered at the tenth anniversary of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2003, “is our answer to their silent question. We have kept our promise. We have not forgotten you.”

Can this vow offer anything more than rhetorical resolution? Perhaps it is the inevitable failure at its heart that accounts for the incantatory power of the phrase “never forget.” To insist on the vagaries of memory is not to suggest we stop telling stories to educate our children, nor to dismiss the public ceremonies by which we mark loss as a community. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize the difficulty implicit in testimony’s exchange. As conscientiously as we take in descriptions of atrocities, the teller tries to rid himself of this plague. The divide of feeling is deep. Out of guilt we insist upon passing down, not memory, but the emotional landscape that sustains its retelling. Yet this wellspring of feeling cannot simply be transferred. No matter how compelling the witness or sensitive the listener, I doubt it can be shared at all.

Can this vow offer anything more than rhetorical resolution? Perhaps it is the inevitable failure at its heart that accounts for the incantatory power of the phrase “never forget.” To insist on the vagaries of memory is not to suggest we stop telling stories to educate our children, nor to dismiss the public ceremonies by which we mark loss as a community. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize the difficulty implicit in testimony’s exchange. As conscientiously as we take in descriptions of atrocities, the teller tries to rid himself of this plague. The divide of feeling is deep. Out of guilt we insist upon passing down, not memory, but the emotional landscape that sustains its retelling. Yet this wellspring of feeling cannot simply be transferred. No matter how compelling the witness or sensitive the listener, I doubt it can be shared at all.

Primo Levi describes the urge to bear witness as compulsion rather than obligation in Se questo è un uomo, the memoir he wrote between 1945 and 1948, published here in 1961 as Survival in Auschwitz. To “tell our story to ‘the rest,’ to make ‘the rest’ participate” he explains in this account, is “an immediate and violent impulse, to the point of competing with our other elementary needs.” For the survivor, Levi argues, revisiting trauma is as likely to erode health as to enhance it. By turns sociological study, psychological exploration, and chronicle of habituation to the extremity of suffering, his book compels through its matter of fact exposition of the author’s ten months in the death camp. But Survival in Auschwitz rarely memorializes. Instead, it communicates to readers a rigorous effort to think through the Holocaust’s schema of violence, an understanding denied the prisoner—whose eyes, Levi comments in his 1986 study The Drowned and the Saved, remain “fixed to the ground by every single minute’s needs.”

A canny retelling of Dante’s Inferno, Survival in Auschwitz offers fable along with fact, a story whose familiarity helps connects us to the author’s experience. As Virgil leads Dante, so Levi guides us through the Hell of our time. By invoking the poet’s language he replaces “the hard cold German phrases” that assault him at Auschwitz with his own tongue. But retelling unwanted visions of the past to ensure others “participate” in his experience only thrusts the writer farther from those he longs to rejoin. Paradoxically, the world of the damned offers him a way back, the torments the medieval poet imagines the tool Levi uses to fathom the reality of the concentration camp, a place without earthly referent. In the same way, though we can never put ourselves in his shoes, we can approach Auschwitz by returning to that oldest divide, the threshold that separates the land of the living from what the author calls here “the house of the dead.”

But the “internal liberation” of the first recollection is only a temporary restorative. Levi admits the self-conflicted character of The Drowned and the Saved when he comments that the book “must be protected against itself” because it draws from memory, “a suspect source.” Or, as he muses from the vantage of a 1980 short story published in English in 2007 as “The Girl in the Book,” “It’s not true that memories stay fixed in the mind, frozen: they, too, go astray, like the body.” The more distant the recollection, the less likely it is to reproduce the integrity of the event. Levi’s apology is not disingenuous: there is a pallid quality to this book, which hovers at the gateway of the surreal world represented in Survival in Auschwitz. Despite its nightmare setting in the “lager,” a place so perversely fantastical as to seem impervious to cliché, The Drowned and the Saved is a gravid memorial with little emotional vitality. An amalgam of Levi’s own stories and “information gained from later readings” and “the stories of others,” the book hovers in a grey zone of emotional confusion. Leached of color, its voice speaks without timbre or accent in wan imitation of more urgent expression. Though Levi resists the consolatory gesture (the easy moralizing that distinguishes oppressor and oppressed in so many second- and third-generation accounts of the Holocaust), his words remain sluggish with sadness.

If even the later work of one of our most gifted thinkers and writers must struggle to communicate, the scores of books and films that return us to the camps from the greater distance of time and person are as often distinguished by falseness of feeling as freshness of approach. The son of survivors, writer Melvin Jules Bukiet enumerates the task imposed upon the children with succinct comic bitterness: “It’s our job to tell the story, to cry ‘Never Forget!’ despite the fact that we can’t remember a thing.” Bukiet’s anger is as distinctive as his recalcitrance; more frequently, contemporary accounts describe without animating the past. Lacking the urgency that moves acts of witnessing such as Survival in Auschwitz, they murmur ritual devotions. Here is the survival of the memorializing genre for its own sake.

If even the later work of one of our most gifted thinkers and writers must struggle to communicate, the scores of books and films that return us to the camps from the greater distance of time and person are as often distinguished by falseness of feeling as freshness of approach. The son of survivors, writer Melvin Jules Bukiet enumerates the task imposed upon the children with succinct comic bitterness: “It’s our job to tell the story, to cry ‘Never Forget!’ despite the fact that we can’t remember a thing.” Bukiet’s anger is as distinctive as his recalcitrance; more frequently, contemporary accounts describe without animating the past. Lacking the urgency that moves acts of witnessing such as Survival in Auschwitz, they murmur ritual devotions. Here is the survival of the memorializing genre for its own sake.

Championing Wiesel’s memoir Night in a January 2006 New York Times essay, critic Michiko Kakutani defends against what should remain—yes, even here, at the site of the death camps—the first principle of any intellectual endeavor: the right to doubt. “When people assert that there is no ultimate historical reality,” she asserts, “an environment is created in which the testimony of a witness to the Holocaust … can actually be questioned.” This reverence runs counter to Levi’s skepticism, whose understanding of the created nature of memoir recalls Amos Oz’s description in A Tale of Love and Darkness. Oz sees the autobiographer as both archaeologist and architect, building a house of memory “out of old stones that he is digging out of the ruins.” For Levi too, compassion does not preclude critical judgment. “One must beware of oversimplification,” the author reminds readers in The Drowned and the Saved. “Every victim is to be mourned, and every survivor is to be helped and pitied, but not all their acts should be set forth as examples.”

But narratives about the suffering of concentration camp victims continue to proliferate, as if fighting for dominance with accounts of more recent genocides. There is something pathological in this unceasing abundance of representations, an obsessive-compulsive rehearsal of torture and degradation whose efforts to understand systemic violence diminish in effect as they increase in frequency. Our American eye has become macabre, indiscriminate in its demands to look upon the wreckage. Reanimations of the Holocaust play out on television alongside fictional dramas that reject crime in favor of the post-mortem and detectives, murderers, and victims cede the foreground to the dead weight of the corpse. We seem to have given up on feeling: treated to an incessant parade of commodities, we become enamored of the still thing. The camera lingers lovingly over the body that demands nothing from us save its own unresponsiveness.

With the exception of a handful of critics—Bernard Susser, Tim Cole, and the much-maligned Norman G. Finkelstein (whose 2000 The Holocaust Industry courageously if crudely addresses the politics of Holocaust compensation) among them—new scholarship does little to counter the indiscriminate repetition of this ruined vision. Invoking the problem of evil as truism and reducing the problem of history to the phrase “never forget,” critical studies fail as do popular efforts to recognize what drives them: not so much the desire to understand intensely painful feelings as the need to simulate such emotional states to remedy our collective numbness. Deprived of the quiet necessary for concentration by the distractions of modern life, anaesthetized by a surfeit of material comforts, we look to heightened states of feeling to produce awareness. Horror offers an emotional purity normal life refuses us. Because it is so clearly absent of reason, we assume that the world of the death camps must be correspondingly fuller in feeling, if only that of dread and despair.

But the Holocaust resists capture. We might do better to expose Nazism to laughter than to continue addressing it as apotheosis of horror, a decision that affords this movement the dignified mantle of the epic. In his 2007 comedy My Fuehrer: The Truly Truest Truth about Adolf Hitler (filmed in Berlin with an all-German cast), Dani Levy wields satire as a weapon to cut Hitler and the Nazi movement down to size. But his parody also suggests we move beyond the ceaseless effort to “understand what we will never understand,” as the film ends by announcing. “[O]ne can today definitely affirm that the history of the Lagers has been written almost exclusively by those who, like myself, never fathomed them to the bottom,” Levi writes at the outset of The Drowned and the Saved. “Those who did so did not return, or their capacity for observation was paralyzed by suffering and incomprehension.” Though the bleakness of the camp approaches the certitude of what Levi calls “perfect unhappiness,” full understanding of experience eludes us. In spite of suffering, the human condition remains one of chronic semi-consciousness.

But the Holocaust resists capture. We might do better to expose Nazism to laughter than to continue addressing it as apotheosis of horror, a decision that affords this movement the dignified mantle of the epic. In his 2007 comedy My Fuehrer: The Truly Truest Truth about Adolf Hitler (filmed in Berlin with an all-German cast), Dani Levy wields satire as a weapon to cut Hitler and the Nazi movement down to size. But his parody also suggests we move beyond the ceaseless effort to “understand what we will never understand,” as the film ends by announcing. “[O]ne can today definitely affirm that the history of the Lagers has been written almost exclusively by those who, like myself, never fathomed them to the bottom,” Levi writes at the outset of The Drowned and the Saved. “Those who did so did not return, or their capacity for observation was paralyzed by suffering and incomprehension.” Though the bleakness of the camp approaches the certitude of what Levi calls “perfect unhappiness,” full understanding of experience eludes us. In spite of suffering, the human condition remains one of chronic semi-consciousness.

On a spring day several years ago I found myself regarding the ocean from the western vantage of San Francisco’s Palace of the Legion of Honor. The sky was windless, the water cerulean blue, the ridge of trees on the horizon etched fine as an engraving. Amidst this serenity, the tableau I stumbled across was grotesque. The plastered forms looked like burn victims wrapped in gauze or mummified relics from Pompeii. Frozen in postures of unrelieved awkwardness, they reproached my joy in the day’s soft brightness.

Most sculptures are designed to engage with the physical space that surrounds them. I picture Richard Serra’s massive ironworks hunkering underneath the vaulted ceiling of Bilbao’s Guggenheim, Michelangelo’s David gazing outward from Florence’s graceful Piazza della Signoria, the conquering eye of Lord Nelson surveying London from his column in Trafalgar Square. This memorial to the Holocaust spurned any such connection. George Segal’s deaf-and-dumb figures did not interrupt the loveliness of the landscape—they rendered it insignificant. And this ill placement was clearly the point, their lack of relief a metaphor for the discomfort we were meant to feel in the face of unremitting anguish.

Undoubtedly I will be accused here of callousness, called selfish, labeled an anti-Semite. Nonetheless, I find this emotional bludgeoning unacceptable. My own links with Europe are attenuated; my grandparents left Russia and Poland at the turn of the century, so I do not mourn the loss of any immediate family in the Holocaust. And I recognize the renewed urgency of testimonial as the last witnesses begin to pass away. Still, I am unwilling to continue participating in an endless ritual of “remembrance” that must, at least in my case, be false. Say what you will: to be goaded into gloom, chided like bad children until our faces assume the appropriate sepulchral cast, is neither to encourage empathy nor to prompt understanding.

When I lived in Israel many years ago I paid a visit to Yad Veshem. Today I can still picture the slender trees planted outside Jerusalem’s museum of remembrance. The flickering constancy of light and shadow through their leaves seemed to me then as eloquent a testament to the lost as any grander monument. I stumbled out of the hushed theater, but twenty minutes of footage was sufficient to understand its obscenity. I had been watching a newsreel of men push corpses down a Warsaw ghetto street. The limbs swung from side to side atop a piled wheelbarrow like any other load. The automatons driving them moved forward in silence, their faces altered and spiritless. Like the “non-men” Levi calls “Muselmänner” in the brutal tongue of the lager, these emaciated figures seemed like those in Survival in Auschwitz to “suffer and drag themselves along in an opaque intimate solitude.”

For Levi, the sight of faces upon which “not a trace of a thought is to be seen” encapsulates “all the evil of our time.” Why then are we so profligate in its reproduction? The camera’s ready-made intimacy invites conspiracy: to watch is to keep company with its persecuting gaze. I had stared at the Yad Veshem footage only to feel a partner in the men’s degradation. Now I conclude that it is not right—under any guise, even that of ethical obligation—to look upon the dead sprawled insensible of the camera’s eye, who, conscious of their capture by its lens, would have suffered a self-abnegating shame in addition to their physical humiliations. Begged to further the cause of historical documentation, how many of us would will our own bodies to such a display? To my mind our unceasing exposure to photograph, fiction, and testimonial raises more questions than it solves. Habituated to the language of apocalypse, we become facile with horror, marshalling up a familiar queasiness with each reminder of indecency.

Atlanta’s compact downtown is made expansive by a ring of skyscrapers that circle it like trees and between whose heights plenty of sky remain visible. The William Bremen Jewish Heritage Museum, which sits south of the city center and west of its graceful metropolitan avenues, is a low-slung building without a façade. Its austere geometry is typical of the generic modernism of much post-1960s architecture. Still, its severity jars in the context of these wide slow streets. The homes here are a century old. Lived in continuously rather than preserved as historic sites, they possess an easy elegance that tempers the walker’s envy of their privilege. To walk by them is to feel time stretched to a larger amplitude as the soft metronomes of veranda chairs rock in deliberate, regular rhythm.

Islanded by its modern architecture, the Bremen Museum is estranged from such equanimity. A smallish building, it boasts ample parking but few surrounding trees. From outside it seems not so much secretive as expressionless in the manner of federal buildings. Its blank front recalls Jewish tradition’s tendency to favor self-scrutiny over social negotiation, to make self-distinction rather than affiliation the object of examination. Too, in this place concerned with preserving the past, the proscription against graven images still carries a certain weight. Many Jews would recognize without being conscious of doing so that what might appear to be a closed quality—the building’s refusal to assimilate to the architecture of its surroundings—is not designed to cast aspersion on others but only to encourage the inward turn toward reverence. But it is not difficult to see how people unfamiliar with this way of locating the self in the world might translate distrust of decoration into dislike of their own society. When you cross the threshold and pull open its heavy windowless door, you feel as if you are leaving Atlanta far behind you. Perhaps a more ecumenical invitation would educate more visitors. I wonder what kind of gesture it would have been to design a structure consonant with the history of the city and its mix of cultures: how might this building look were it to insist upon Jewish rights of residency while acknowledging the Middle Passage along which the predecessors of some of the city’s black inhabitants suffered and died?

Although the Bremen is not in conversation with its locale, the museum speaks to sites for the preservation of Jewish culture elsewhere. Inside there is a very handsome lecture hall built to accommodate several hundred listeners and two wings of galleries. One door leads to a temporary display dedicated to the city’s Jewish residents, but the largest space is devoted to the museum’s permanent Holocaust exhibit. In here you wind through a series of small chambers connected by narrow hallways. The interior walls detail, in text and photograph, the history of modern German anti-Semitism that culminates in the Shoah. The exhibit’s design is predicated upon this unrelenting chronology. Its rooms are without alternative egress, sequential rather than adjacent, so you walk through them in the single direction the narrative permits. No doubt this lack options is designed to remind visitors of the constricted, ever-narrowing aperture Europe became for Jews during World War II. Coupled with the building’s low ceilings, dim lighting and grim portraiture, the inviolate chronology provokes hopelessness and claustrophobia in equal measure.

Its spatial determinism also mirrors the institution’s temporal rationale. Like other museums of remembrance, the Bremen presents history as inexorably linear. Its chronology plays out backwards from the apocalyptic moment of the Shoah, which, as origin point, becomes curiously ahistorical. Such retroactive dating provides the frame within which, as Michael André Bernstein argued in Foregone Conclusions (1994), the “entire experience” of European Jewry “prior to the Third Reich is judged.” My sense is that the Bremen, in situating the Holocaust as the anticipated outcome of a course carried through to completion, wishes to accord the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews coherence and dignity. Certainly the funerary rhythm of its procession of events lends the whole a tragic grandeur. Unfortunately, this tidy progression also echoes the quasi “logical” rhetoric of the Final Solution itself.

As in similar institutions across the country, the exhibit is a dirge; its ritual of “remembering” keeping us trained upon the end we have anticipated from the first room’s display of photographs. Paradoxically, the urgency of its timescale encourages a suspension of faculties rather than a quickening of them. You walk through the rooms, look intently at the photographs and read the scripts, only to be overtaken by inertia potent as incipient nightmare. The air feels torpid, a vacuum simulating the silence of the Shoah. You look again at the faces of the dead, but they have been effaced by the devastation of History writ large. This epic sweep blots out the quotidian life the museum is dedicated to preserving—the excited mix of Yiddish, French, and Polish you might have overheard at a Warsaw dinner table, the sweet butter linzertorte you could have tasted in a Berlin bakery. What gets lost may seem slight, but it is the kind of detail that allows us to linger upon the particulars of distinct lives: the plaid skirt a daughter wore in her last photograph, the scuffed suitcase a father filled with the family’s prized possessions, the book upon whose flyleaf the date of a bar-mitzvah, penned in spidery script, speaks of inspiration and of blessing.

There is little equivalence between public forms of mourning and the private expression of grief. Deep feeling—for a person, a place, or a past—is oblique and hallucinatory, its words spoken sotto voce, its presence a ghost shadowing us on our daily routines. Collective mourning proclaims what it misses, hoping volume and magnitude compensate for absence. In monumental architecture, the permanence of granite and steel is a protest against the fragility of memory. The garden of New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage is filled with tons of stone, the polished surface of the Vietnam Memorial engraved with thousands of names. For a time, the space once occupied by the Twin Towers was illumined with a million kilowatts of electricity. Its radiant blue beauty climbed skyward with more than a hint of that power’s threat.

There is little equivalence between public forms of mourning and the private expression of grief. Deep feeling—for a person, a place, or a past—is oblique and hallucinatory, its words spoken sotto voce, its presence a ghost shadowing us on our daily routines. Collective mourning proclaims what it misses, hoping volume and magnitude compensate for absence. In monumental architecture, the permanence of granite and steel is a protest against the fragility of memory. The garden of New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage is filled with tons of stone, the polished surface of the Vietnam Memorial engraved with thousands of names. For a time, the space once occupied by the Twin Towers was illumined with a million kilowatts of electricity. Its radiant blue beauty climbed skyward with more than a hint of that power’s threat.

The largesse of public mourning reminds us of the breadth of loss, but it also exempts us from attention to detail. Enormity of scale possesses its own momentum. I learned this on a visit to the Hoover Dam in Arizona years ago. The fluted granite walls of this funnel rise to a curved rim hundreds of feet above the river floor. From far away the dam’s parabola is companion to the sky’s weightlessness. But lean over the rim, and the steep slope drags you downward. Falling from the dam is the same as stepping off a skyscraper fifty-five stories high. One glance at the seven hundred foot drop and vertigo seizes you: the convex stone pulls away, its dizzying curvature carrying sensation with it. The sounds of traffic and the shrieks of children, the shimmer of heat on the freeway and the rough cement under your hands: all vanish in this freefall.

To stand in the shadow of a memorial is to experience a similar loss of perspective, and with it, the small certainties of your own footing. The size of most monuments accords them the same visual draw as the dam’s steeply inclined sides. How easy it is to pay our respects to these massive tombs and in doing so lose sight of the lives they betoken. “Awe” and “awful”: the syntax of destruction and beauty twine, uncomfortably close. Voyeurs, we enjoy an aesthetic response to a problem that demands a moral focus. The opiate of feeling binds us together superficially but dissipates as quickly, depriving us of mindfulness. Nor does the splendor of these obelisks permit the peripheral vision of memory, more insight than spectacle.

Our feelings for the lost do not require the constant synchronizations that bonds with the living demand, but they are neither straightforward nor impervious to change. Where do we see these complex affiliations mirrored in public buildings? The vertical sweep of Oklahoma City’s memorial and the stony horizontals of New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage possess an imposing but intractable majesty. Even the colossal wrecks of the pyramids feel more approachable, their vastness reduced to human scale by the paraphernalia of everyday life littered throughout their underground rooms, cooking pots and water containers strewn haphazardly alongside jewelry for the gods. Our modern memorials offer no such invitation. In their cavernous spaces, ordinary tokens of remembrance seem out of place. Those designed as secular are intended to gesture toward inclusion. But without the tempering beneficence of religious purpose, they mark only the bewilderment we feel in the face of acts that defy faith altogether. No presence hovers inside them, only mourning without solace, the grief we hold for the dead we cannot bury.

Even in photographs, the small memorial New York City resident David Cohen improvised for the victims of the September 11 bombing evokes more feeling, to my mind, than the airless magnificence of the larger structures we have consecrated to disaster. His store Chelsea Jeans stands near where the World Trade Center used to be. Rather than clean up the debris, Cohen let the damage stand. The glassed window invites passersby to peer inside at what is essentially a grown-up’s diorama. The date is inscribed in block capitals at the top of the wall; florescent light, warm-looking in the tomb-like room, illuminates racks of t-shirts and jeans. The slate colored shirts are stacked, as Michael Kimmelman wrote in 2002 for the New York Times, like “lined-up headstones.” A fine, blue-grey dust covers them all. The critic sees in these clothes a hint of George Segal’s “preserved” figures. Though artful, this observation seems wrong: Cohen’s store does not presume to display, let alone confront or provoke. It is just a frame for memory; the way the foundation of a house burned to the ground might still retain some feeling of the lives it sheltered. The shop’s quietness resonates with palpable human sorrow. In its tiny space there is ample breathing room for reflection. I stare at the fallen ash, which, like the dust that collects on the surface of a bureau, possesses a softness my fingers yearn to touch.

I crave the restoring intimacy of the personal, the modesty of old Polaroids rather than the masterful images broadcast on television in the days after the September 11 bombing. Disaster does not possess the coherence of art. Loss burns and dissolves detail; departure leaves stupor in its wake. The 9-11 films—the New York skyline bereft of its highest towers; the silhouette of a fireman walking through wreckage; the stately slide of buildings falling to earth with a curious grace—are perverse. I want gesture and voice, the small space and the close angle. A ceramic mug of cold coffee, its white surface stained with the lipstick imprint of a woman’s mouth. A portrait framed by a child’s blurry thumb. A wrinkled shirt still scented by a man’s skin. Bottles. Cobwebs. Rust.

I confess I do not understand the decision to call the austere garden of New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage a “living memorial.” To me this place seems weighted toward the desolate, open to the air but bereft of oxygen. The heavy rocks have been strewn with the guilelessness of an avalanche. The stunted trees, designed as a tribute to endurance, look threatened rather than coaxed into surviving. There is something false in this “garden,” something stifling in its stark drama inimical to memory’s invitation. Like other American sites dedicated to remembrance of the Shoah, this arid place recalls not only the devastation of the catastrophe but our own distance from it. Because Holocaust memorials in the United States are quite literally out of place here, they do not so much evoke a lost presence as elaborate a central absence. Metaphor without a referent, they must imagine what they mourn.

I bade my troops once encamp upon a town That enemies had razed in ancient times. We pitched our tents and slept upon its site, While under us its former masters slept…. They’ve changed their palaces for sepulchers; They’ve moved from lovely mansions into dirt. But should they lift their heads and leave those graves, How easily they’d overwhelm our troops!” Never forget, my soul, that one day soon This mighty host and I will share their doom.

– Samuel the Nagid (993-1056)

The sanctification of trauma is our collective misfortune. Let me say here, clearly and calmly, that at this point I believe its ethical consequences are too debilitating to warrant its continued blind persistence. The culture of mourning, which swells in strength as we recede from the Shoah, has become a ritual largely emptied out of genuine feeling. Outcry ensues each time someone begins to question its repetition, but have we not been raised to put equal faith in the spirit of inquiry? When does memorial supplant rather than supplement memory? What does it mean to “remember” a disaster, and what are the consequences for future generations of doing so in perpetuity? At the opening of the twenty-first century, the rationales we offer to stay judgment turn to excuse. We have grown up assuming our study of disaster will remind and so ward off the worst consequences of racial hatred, but a half-century of renewed genocide only provides evidence of the devastation “ethnic cleansing” continues to inflict around the globe. We have made the Shoah exemplary, insisting upon its singularity of magnitude, but when other atrocities are overshadowed by its reach and scale we create a moral dilemma that obliterates the satisfaction of our own accuracy. And surely Primo Levi’s insistence on mourning the individual rather than the mass underscores the perversity of using a comparative scale to “weigh” acts of torture and genocide. The Holocaust is the supernova of catastrophes; dazzled by its afterimage, we are blind to the tragedies that unfold in front of us. The word itself has become an unyielding monument, imperious in its drawing power. Black hole of loss, it absorbs everything into itself.

As a term of practical value in political negotiation (need it be said?), the Holocaust has lost its efficacy. Its invocation in the current Middle East conflict is corrosive: Jews cannot help but wince at the cynicism of ultranationalist anti-Semitic groups who mock its use, while others are quicker to understand its rhetoric as inflationary rather than a history lesson designed to defuse. And while anti-Semitism has thankfully not since the close of WWII developed into genocide, the call to restore the broken world that is one of Judaism’s most inspiriting tenets compels us to treat any act of ethnic loathing as if our own survival were at stake.

As a term of practical value in political negotiation (need it be said?), the Holocaust has lost its efficacy. Its invocation in the current Middle East conflict is corrosive: Jews cannot help but wince at the cynicism of ultranationalist anti-Semitic groups who mock its use, while others are quicker to understand its rhetoric as inflationary rather than a history lesson designed to defuse. And while anti-Semitism has thankfully not since the close of WWII developed into genocide, the call to restore the broken world that is one of Judaism’s most inspiriting tenets compels us to treat any act of ethnic loathing as if our own survival were at stake.

Though it spawn concert and anniversary exhibition and even, as at the National Memorial in Oklahoma City, sell t-shirts, we must not participate in the commercialization of disaster. Instead, we must pry loose our hold on the assumption of perpetual adversity. Surely the habit of refusal such divisiveness encourages is not a posture we want our children to maintain. We need to recognize that continual efforts to call attention to the Holocaust as if it were a singular exception to an all-too common fate carry with them the very ethnocentrism we have been at pains to indict. It is a kind of arrogance in any people to cherish the evidence of its own troubles as distinctive, above and beyond the prosaic difficulties that others face. There must be many standing in the long shadow of Holocaust memorials who feel their own past has been consigned to oblivion. Allowing ourselves to be swept away in the grandly isolating mode of tragedy possesses a certain appeal. But if we begin by assuming mistreatment or contempt, we make the work of keeping an open heart that much more difficult.

If we wish to continue building such memorials, let us do so with more generosity and openness, with an attitude of receptiveness and some humility. Make them provisional rather than permanent—moments of silence for the dead rather than a perpetual mourning that inevitably deteriorates into self-pity. Temper them with the acknowledgement that suffering is not a commodity of scarcity anywhere on earth. Install them so that they encourage an attitude that is genuinely self-critical as well as censorious of the wrongs others have committed. And finally, place them alongside the memorial-graves of others so that we when we repeat those incantatory phrases of promise and pain we speak them in the accent of the poet a thousand-years dead who did not forget, in a moment of victory, to chant Kaddish for all of the dead.

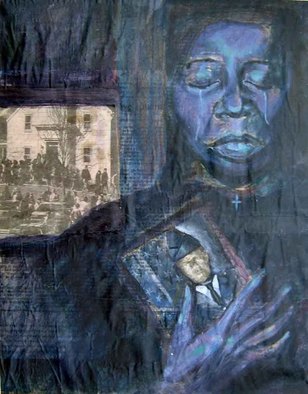

Images from top: Homecoming, Prayer for the Oppressed,Tears of Angels, Shadows That Weep For Shadows,Martyrs and by Heath Matyjewicz. credit2=Images from top: and The Kiss by Heath Matyjewicz.

%%

my site Programs Alternatives

OCI AML2 and OCI AML3 were obtained from DSMZ, regularly authenticated by NPM1c expression, and genetically modified in house does lasix make you tired

%%

my web page :: Best Adhd Medication For Adults With Anxiety

%%

Here is my web page … dealers (https://hotel-semiramis-marrakech.com)

%%

Review my web blog: Bets (Climakind.com)

%%

Feel free to visit my blog post – oracle netsuite consultant

%%

Here is my web page: horse betting – Muriel –

%%

Also visit my web site – Netsuite Solution Consultant

%%

Check out my website … Best Cream Night

%%

Feel free to visit my blog :: undiagnosed Adhd In adults

%%

my website – Gambling addiction, Customjewelrybydesign.com,

%%

Here is my web page; erp consultant

%%

Feel free to visit my web site; horse betting (https://www.apolloristorante.com)

%%

Feel free to surf to my homepage – implementations

%%

Feel free to visit my site Netsuite consultants

%%

My web site: Adhd in Adults treatment uk

%%

My web blog … Day cream spf 30

%%

Have a look at my web site; Netsuite Consultant

%%

Here is my web page: adult adhd Symptoms women

%%

my blog post: online poker (https://nassaufire.com)

%%

Also visit my web site adhd Medication Ritalin

%%

My web-site :: sports – Odell –

%%

Also visit my web site: Adhd Adult Diagnosis

%%

Feel free to surf to my homepage … Consultants

%%

my website; Best day cream

%%

My blog post psychiatric assessment London

%%

Here is my webpage: seo service uk

Many bodybuilders who are looking to avoid testicular atrophy take Nolvadex with an aromatase inhibitor during the last few weeks of their off-cycle PCT plan in order to boost natural testosterone production. tamoxifen and vitamins to avoid Despite not having a definable cause, these men may respond to treatment.

tamoxifen

See Sperm Penetration Assay. clomiphene for sale I am no expert, but here s what I think ; And sorry if I am repeating PPs.

2007; 34 549 553. buy clomid

That s our commitment to you here at GenericsWow buy priligy generic fraud 5 at baseline to 29 at end-of-study dapoxetine 30 mg ; 0

Molds thrive in warm, damp areas, which also includes showers and bathrooms generic priligy